Invisible Chains: Photography’s Ingrained Assumptions

For this writing commission Lewis Bush looked at the way in which Covid-19 reveals several very significant limitations in the way most photographers think about the medium and what it can and should do. One of these being the idea that proximity produces insight and also the notion that showing something goes any way towards explaining its causes and consequences.

His new writing looks at the visual tropes emerging in the converge of the pandemic and these ideas and highlights what we can and should learn from this crisis as photographers.

Invisible Chains: Photography’s Ingrained Assumptions

by Lewis Bush

In his allegory of the cave, Plato describes a group of prisoners living their entire lives chained in the darkness. Shadowy outlines play on rocky walls, providing the prisoners with their only sense of reality, and they remain entirely unaware of the world outside which created these flickering forms. For Plato, a philosopher was someone who broke their chains and departed from the cave forever.

Whenever photography has been a witness to a prolonged and major news event, it has tended to generate a set of visual motifs specific to that story. The global ‘war on terror’ for example gave us the ever-repeating tropes of the aftermaths of terrorist attacks, soldiers enshrouded in clouds of sand and dust, hooded figures kneeling in orange, flag draped coffins, and so on. The creation of these tropes was evidently the result of many factors, choices and filters,[1] but two were particularly important amongst them. One was the specific visual aspects of that conflict, for example it’s locales, belligerents and tactics, and the other one was the particular possibilities for photography in the context of the event, possibilities partly dictated by specific practices like the military system of journalistic embedding and the intentional targeting of journalists by insurgent groups. The images that define the ‘war on terror’ were, in other words, as much a representation of what was photographically possible, as they were the a matter of the best way of visually representing, much less explaining, the subject that was being recorded.

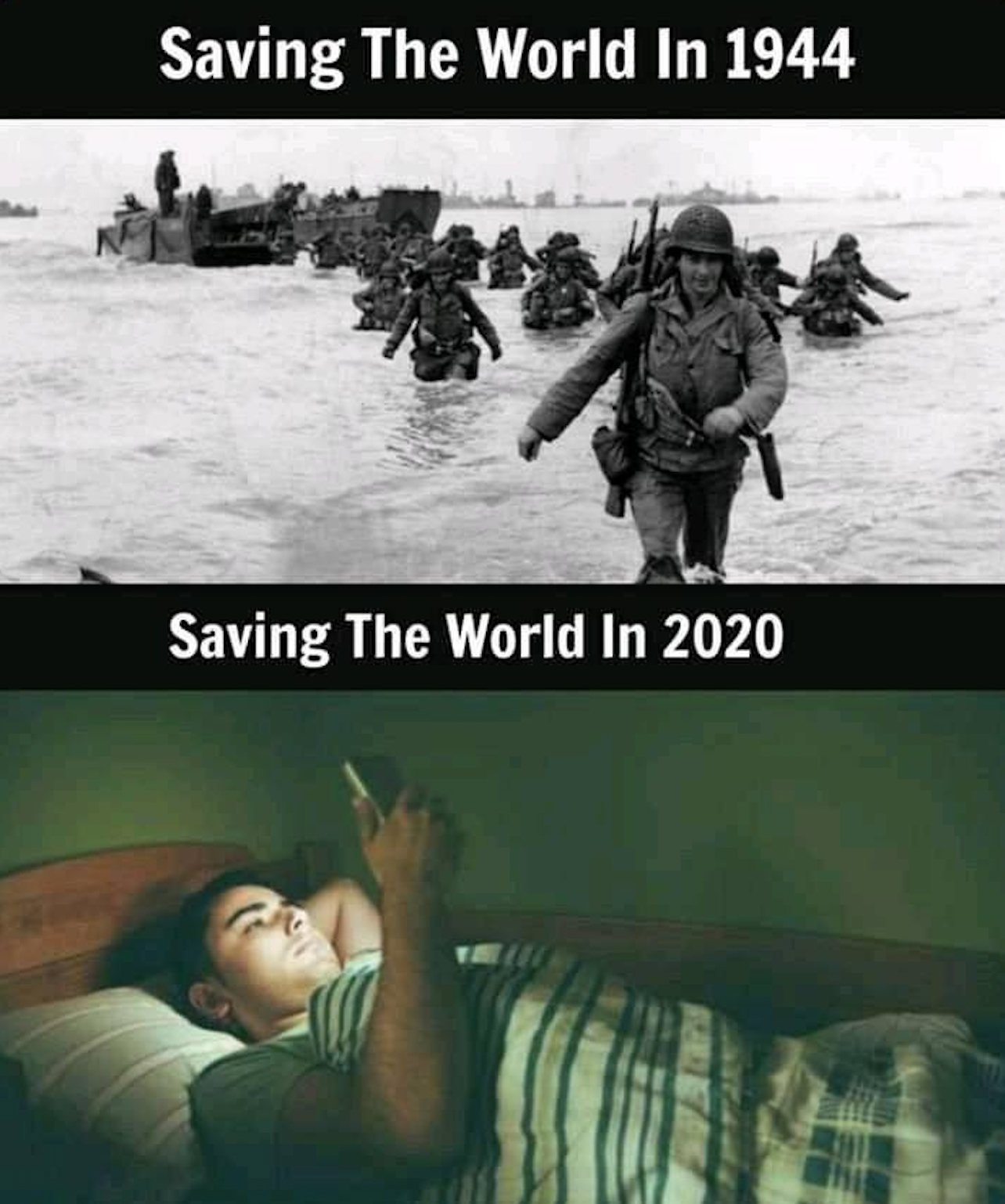

The coronavirus pandemic has been no different in its generation of a set of specific visual tropes, motifs or clichés. I do not doubt that you have already seen many of its examples; People photographed behind their windows and socially distanced on their doorsteps. Photographs of normally bustling landmarks reduced to emptiness. Portrait sessions and other interactions conducted over videoconferencing software. The compressive properties of telephoto lenses manipulated to suggest packs of people crowded dangerously together. Medical staff made anonymous and threatening by layers of personal protective equipment. The list could go on, and on. These image types have been repeated endlessly over the last six months, forming an insidious after image in our collective mind’s eye. They have become an indelible memory of the strange times we have been living through, whether or not it is instructive to remember in these ways. Why, I often ask myself, have few more nuanced responses emerged?

The emergence of such tropes is a clearly a problem with any major news event, but with coronavirus the lack of variety in its representation, and the lack of insight that many of these approaches offer, seems more pronounced than ever. This despite the crisis forcing many of us to spend far more time reflecting on things than we would perhaps have liked, ample time one would imagine for photographers to come up with more nuanced visual strategies. One of the explanations I think is that these images, as much as being a reasoned way of visualising the pandemic, of showing the essential ‘reality’ of it, are also very definite product of the unique limitations that the pandemic places on photography and photographers. In particular and most noticeably the proscriptions in many places on free movement and close contact with other people, two things that photographers rely on more than many of those employing many other means of recording contemporary life.[2] In other words, the photographs that have emerged from the pandemic are again often far from an answer to the question of how best to represent and explain this event and its consequences, and they are much more than usual an answer to the question of what it is possible to photograph under these circumstances.

These visual motifs and tropes are for the most part lacking the perceptiveness they often claim. They provide little or no new insight either into the specific epidemiological profile of the virus, the remedial efforts being put in place by governments and health authorities around the world to stem it, or the personal, social and economic consequences that have resulted from these efforts. We might assume this is because these things are simply beyond photography’s technical capacity to show, but in reality, I suspect it is more difficult than that. The truth I feel, is that these things are actually beyond our imagination to show because we are at every turn constrained and restricted by deep rooted and narrow beliefs about how we should best use photography to explore an event like this one, and all the more constrained because we are for the most part unaware of these constraints. Recognising this could however be an interesting opportunity, because by reflecting on the prevalent clichés in the visual record of coronavirus we might be able to identify the outlines of a few of the hidden ideas that silently shape the creative choices we imagine to be entirely our own.

All human practices are underpinned by certain axiomatic truths, beliefs and assumptions that reflect both the perceived nature of the world we live in, and the imagined nature of the world that we desire to live in.[3] These beliefs are not self-evident, eternal or immutable, they are a product of cultural circumstances, and like all beliefs they ebb and flow with time. They are frequently unrecognised and unspoken, and thus seldom subjected to scrutiny, usually becoming matters of discussion only when something reveals a failure or contradiction within one of them, or when two of them come into direct conflict with each other. Amongst the axioms that underpin medicine, for example, are the beliefs that it is desirable to extend human life, and to alleviate suffering, two assumptions which are usually only subject to significant debate when one of these two aims cannot be achieved without severely compromising the other.[4]

In its own right, photography, and in particularly those genres of photography primarily focused on events in the world, is underpinned its own set of apparently self-evident truths. Many of these concern ideas about the correct way to use photography, in other words what it should be able to do that the other representational tools we have available to us cannot.[5] This is significantly a little different from the often-discussed medium specificity of photography, in that these beliefs do not necessarily need to have a direct relationship to the actual technical qualities of photography (indeed sometimes they ignore these qualities altogether), but in many cases originate elsewhere in society and culture, often in ideas which significantly predate photography’s invention. The problem with these beliefs, and the value in exploring them, is that they shape and direct the ways we use cameras and photographs in ways which sometimes prevent us using photography as dynamically as we might, and as a result undermine rather than strengthen the goals we seek. For this reason, if no other, we should try to draw them out and assess quite how useful they are.

Photographers generally show little willingness or ability to even acknowledge that such beliefs exist,[6] but the global coronavirus pandemic has, quite unintentionally, brought many of these axiomatic truths to the fore, by revealing some of the contradictions and inadequacies within them. Perhaps the most important of these underlying assumptions, are beliefs about the way we derive knowledge from the world, something which we might call the Axiom of Sight. With the gradual emergence of empiricism in Europe between the twelfth and eighteenth centuries, direct sensory experience came increasingly to be viewed as the primary source of information about the world. But of the senses, sight quickly came to occupy a place as the first among equals. Visual technologies like photography helpfully extended what human sight could perceive, cementing it’s pre-eminence, but they also created a paradox. These technologies which were often conceptualised in terms of biological optics, also made it increasingly impossible (for scientists at least) to ignore the vicissitudes and shortcomings of human vision. This recognition seems to have penetrated far less into wider culture, and we have inherited an awkward cultural legacy from these foundations, which still invariably equates seeing with knowing.

The vast majority of photographers are still trained in a tradition rooted in the idea that a photograph of something explains to a viewer why that thing exists, how it functions, why it matters to their life, why and how they should do something about it. But very few photographs are capable of even accomplishing a single one of these tasks, and most of those that do exist in the realm of highly functional, technical images (for example medical x-rays, satellite images, surveillance footage) which very few of us spend much time looking at or thinking about.[7] The majority of art and journalistic photography relies on the strategy of either depicting something aesthetically pleasing or morally troubling to engage audiences with an issue, and it is usually believed that in doing so viewers are motivated to action. In practice such images are just as likely to dull viewers into a sense of apathy or paralysis, less because of the dubious phenomena of photographic ‘compassion fatigue’ but often more because such images seldom offer viewers clear means of recourse or action, and given no outlet any sense of outrage or motivation these images might generate is more likely to slowly stale away inside of them.

Photographic coverage of the coronavirus pandemic reveals this most acutely, in that most of it transmits very little information about the virus or its consequences, beyond the things that we largely already know. Arguably this redundancy is made all the more extreme because of the truly global nature of the crisis, and the fact that many of visual tropes to which most photographers have retreated depict situations that many of us have direct personal experience of. This state of affairs suggests at a second foundational belief closely related to the first, which we might call the Axiom of Effects. This is the emphasis on photographing the highly visible consequences of news events and social phenomena, more often than not these consequences being the ‘victims’ of these things, rather than attempting to reveal the root causes or perpetrators of societal problems and ills. Like the previous axiom, this one has a long lineage, running back to and beyond the emergence of prose journalism and its role in the creation of an informed and engaged citizenry, able to participate in the discursive space that Jürgen Habermas dubbed the public sphere.[8] In this space, a citizenry armed with knowledge derived from journalism would engage in informed debate about the issues of the day, reaching decisions which would allow them to shape the political direction of their communities.

The emergence of photography as a news and documentary medium built to a large degree on this existing understanding of journalism’s purpose. We can see it particularly evidently in the use of photography by early visual advocates for human rights and social reform, like Jacob Riis, Alice Seeley Harris and Lewis Hine, who forged the template that many still follow. Yet what we often forget when citing these examples is that their images formed only one part of their battery of communicative techniques, often depending on extensive narrative context in the form of firebrand speeches and extended texts in order to shape their meaning. The effectiveness of photography for these campaigners lay again largely in its ability to bear witness, to shock, and more troublingly in some cases to excite and thrill. It did not lie in its ability to explain, a fact that we seem today to have become curiously impervious to recognising. Even the most successful photo-essays of photojournalism’s golden age, so often held up as exemplars of purely ‘visual’ communication, relied on their pairing with extensive texts, which provided the explanation of the subject matter that the images never could not. Photography shows only a fragment of an event, and even then, usually only those events that lend themselves to the spectacular or the easily visualised. A photography cannot readily show badly formulated public health policies come into existence, nor can it help us understand why government corruption or ineptitude, at best it might manage to show it.[9]

A third and for now final belief we could dub the Axiom of Transparency, the still prevalent idea that the camera is a transparent window on the world. This idea again is one with roots beyond photography, pre-dating at least the industrial revolution, and exists today as a widely held instrumentalist belief that technologies are essentially neutral tools, that stand apart from social, political, or even aesthetic concerns, but somehow untouched by them. Proponents of this belief (which in truth is almost all of us) view technologies as rational embodiments of principles that are held to be universal, like the desirability of greater speed or efficiency, and the assumed universality of these principles is assumed to also make these technologies universal across time and space. The reality, as thinkers including Lewis Mumford and Donna Harraway have shown these technologies embody the knowledge that makes them possible, and embody specific cultural beliefs and assumptions about the world. Photography for example employs single point perspective in a way which emphasises the primacy of a viewer’s perspective, a ‘god’s eye view’ as many observers have described it, and segments and interiorises that view into the space of a four sided frame. This is not a natural or accidental design, it a choice with roots in western ideas about vision and art.

It is true that most people today would regard the idea ‘that the camera never lies’ to be utterly naïve, and many would also recognise that it does not a pure and unmediated relationship to the things that it depicts. But what is the curious that the same people who would profess these views, in their interactions with photograph and cameras, express exactly this belief unspeakingly through their actions. The camera is still instinctively regarded as a transparent window on the world, we invariably take its images at face value, and it takes active engagement to consider and recognise its well-known capacities for deception and its ability to influence the situations it depicts,[10] much less the subtler ways that embodies specific ideas about the world. Put simply we have been programmed to take the camera’s images at face value, and that programming takes enormous effort to overcome. We can see this again in the abuse of the compressive properties of telephoto lenses by unscrupulous photographers, to suggest crowds where clearly none exist.

This text has not intended to create an exhaustive list of these axioms, or even offer a comprehensive discussion of the few that I have speculatively attempted to identify and name. Nor is it in itself an attempt to challenge or change them, because as has hopefully become clear these underlying assumptions are far too deeply rooted in the history of photography, and the broader history of western thought to be dislodged by a single, short text. Even once aware of them, they still remain the well-worn furrows to which an unguarded mind readily returns. Like ruts in a road, they are too magnetically familiar and too easily travelled, for us to simply forget or dismiss them. They will remain our default mode of thinking for an indefinite future, until new ways of thinking emerge which dislodge them, just as they in turn dislodged earlier pre-modern ideas rooted in beliefs about the spirit world and the divine.

I think however that is worth noting that that these previous intellectual revolutions were invariably fomented by wider social stresses, like mass outbreaks of disease, religious reformations and internecine wars. I do not believe that the current epidemic will be the trigger for a wholesale revolution in the way we think about the world, but it might be one factor amongst many that start us on a process of reassessing the usefulness of the beliefs that have shaped our societies for centuries. While we wait for new alternatives to hint at themselves, we each at least address the deficiencies of our current beliefs by forcing ourselves to engage more actively and thoughtfully whenever we make, use and see photographs. We can each choose to consciously recognise the ways that photography is underpinned by a set of beliefs about the world, and we can recognise the fact that these are culturally formed ways of thinking, not incontrovertible and universal truths, even if it we still struggle to imagine alternative ways of thinking.

In doing this, like the prisoners of Plato’s cave, we force ourselves to the knowledge that there are other ways of being outside of the narrow world which we can actually perceive, even if we cannot yet break our chains, and depart our cave in search of them.

[1] For a detailed study of the filters and concerns that shape the selection of images in photojournalism see Zeynep Gursel’s 2016 Image Brokers, an anthropological study of key sites and actors the industry.

[2] Although it’s worth noting that at least some of the photographers have produced these stereotypical projects appear to have broken UK law to create them. During lockdown there was a short and unambiguous list of acceptable reasons for leaving home. Conducting work as an accredited journalist was one of them, but pursuing independent creative projects was not.

[3] For this piece I focus primarily on very ‘western’ examples of these axiomatic beliefs, in part because these are the ideas that I am most able to identify, but also because photography as we understand it today emerged from a milieu formed by these beliefs.

[4] The tensions between these two goals often publicly emerge in High Court cases, particularly highly emotive cases revolving around the care of seriously ill children. See for example the 2017 High Court case over Charlie Gard, and the 2018 case of Alfie Evans.

[5] It’s worth noting again that this argument comes from a heavily western perspective. While not denying the existence of distinct modes of thinking about photography in other parts of the world

[6] A few photography critics and theorists have however. Jonathan Crary’s Techniques of the Observer is a good example exploring the relationship between the emergence of photography and cultural attitudes towards sight. Lorraine Daston and Peter Galison’s 2007 book Objectivity also includes interesting reflections on this.

[7] This fact also gives emphasis to the untruth, still routinely perpetuated by many people who should know better, that photography is a ‘universal’ or ‘democratic’ visual language. At best it is a constellation of languages and their dialects, some bearing a limited relationship to one another, others about as related as Chinese is to French. To understand the interpret the meaning of an orthographic satellite image requires an understanding of very different visual codes and technical principles than interpreting a photojournalistic photo.

[8] Jurgen Habermas, The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere: An Inquiry into a Category of Bourgeois Society (1962)

[9] See the work of Alex Navaly, the recently poisoned Russian opposition politician and anti-corruption campaigner for a rare example of photography used very much on its own terms to assemble compelling evidence of systemic corruption in Vladimir Putin’s United Russia party.

[10] The use of telephoto lenses to misrepresent the proximity of groups at publication locations is an example of this, which has taken in many including even quite experienced photographers.

About the Writer

Lewis Bush works across media and platforms to visualise the activities of powerful agents, organisations, and practices. Since 2012 his practice has explored issues ranging from the aggressive redevelopment of London, to the systemic inequalities of the art world. Recent works include Shadows of the State, which examines the democratic deficit of intelligence gathering, and Wv.B which examines the dark histories of space exploration. Bush has written extensively on photography, and since 2011 he has run the Disphotic blog. He has curated a number of exhibitions and is course leader of MA documentary photography at London College of Communication.

Image Credit: Saving the World in 1944 / Saving the World in 2020