Moving towards rupture, resistance, and refusal in Black moving image works

For this writing commission Jamila Prowse asks the question – In these isolating, politically rife times how can photography and moving image be used as a source of hope, as a way of collectivising Black communities, as a way to hold each other digitally and create space for both each other and ourselves? Her new essay analyses theories around the rifeness of images of Anti-black violence, situating the creation of images of Black joy and abundance within this context as a way to question how Black artists envision and imagine new potentialities for a world in which Black lives are not only valued but celebrated.

Moving towards rupture, resistance, and refusal in Black moving image works

by Jamila Prowse

On 25th May 2020 a forty-six year-old man by the name of George Floyd was murdered by a police officer in Minneapolis. The graphic video showing the moment Floyd’s life was taken from him was subsequently shared online, sparking a resurgence in public support for the Black Lives Matter movement. What the video reveals is something that is maddening and heartbreaking, but unsurprising to Black communities the world over: what Tina Campt terms the ‘statistical probability of Black death’. The viral quality of the video documenting George Floyd’s murder exposes that Black people are not afforded sanctity in life nor in death. For many, the denial and avoidance of the positioning of Black people throughout the world was brought to a head. Here, along with the racially motivated killings of Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery, Tony McDade, Dominique “Rem’mie” Fells, Riah Milton and countless others during 2020 and beyond, provided stark and undeniable evidence of the devaluing and disposability of Black life. Yet, this is a lived reality which cannot be denied, buried or avoided for Black communities.

Christina Sharpe, creates a ‘conceptual framework for living blackness in the diaspora in the still unfolding aftermaths of Atlantic chattel slavery’ through her theory of “the wake”. “The wake” holds multiple meanings, but is an overarching acknowledgement that slavery continues to shape and dictate the structuring of contemporary society. Living through this wake as a Black person, means to ‘live near death’, always aware of its looming threat. Thus, in the viral sharing of the loss of another Black life at the hands of the state, the inescapability of premature Black death was once again made visible. As a mixed-race, light skinned person, who is racially ambiguous, living through “the wake” does not mean staring death in the face in the same way as it did for my father or his ancestors. My light skin affords me the privilege of moving through the world without the continual probability of violence enacted against me. Still, as I sat glued to my screen at the end of May, I became overwhelmed and debilitated by the complex trauma of seeing daily visual reminders of the close proximity of my ancestry to death. For my father this proximity was a lived daily reality, with many of his close family losing their lives prematurely as a result of violence, poverty and sickness.

The pain and anger that my father carried with him throughout his life may well have been a contributing factor to his death in 1998 at the age of forty-four. I was three when my father passed away, I am now twenty-five, and reckoning with how little has changed in the world since I lost him dad twenty-two years ago, how much of the atrocities that broke his heart still exist, is a painful knowledge that is by no means unique to me. How do we reckon with this pain, that was carried by our ancestors and continues to live unrelentingly on in the world? In Sharpe’s words: ‘What does it mean to defend the dead? To tend to the Black dead and dying: to tend to the Black person, to Black people, always living in the push towards our death?’ It is this question that guides the following essay. If we are to reckon with, to live through, ‘the contemporary conditions of Black life as it is lived near death’, we have to have routes and methodologies of collective resistance. I am interested in what Sharpe calls the ‘possibilities for rupture’ which exist within the resistance of Black communities living expansively, fully and unapologetically. Of the daily resistances and ruptures which are inherent parts of Black life.

Towards the end of May my good friend Calum Jacobs suggested that a way to process, to honour, the collective trauma we were experiencing, would be to surround ourselves with the writing, thought and art of Black thinkers, artists and academics. I have always been interested in art as a mode of resistance. Art as a sphere of imagining alternative worlds, of envisioning possible futures. I am drawn to moving image and artist filmmaking as a site for the imaginings and limitless potentialities for Black life. No less, in 2020, when moving image presented itself as a resolve of lingering solace. Underpinning the following thinking, is a consideration of the moving of image: the tense in which it is viewed, the tense in which it is located. Informed by the thinking of Tina Campt, who notes ‘To me it is crucial to think about futurity through a notion of “tense.” What is the “tense” of black feminist future?’ Simultaneously, I am preoccupied with Christina Sharpe’s answer to her own question outlined above: ‘What does it mean to defend the dead?’ ‘It means work. It is work: hard emotional, physical, and intellectual work that demands vigilant attendance to the needs of the dying, to ease their way, and also to the needs of the living.’

What follows are a series of encounters I had with Black moving image works between May and August 2020. I had these encounters at home, via the 11-inch screen of my laptop, a tiny portal which cannot contain the expansiveness of the artworks I came into contact with. What are these moving image works moving towards? How is moving image situated in relation to futurity? How does it think us out, away from, and beyond the present moment?

Some notes on location before I begin… (after Jemma Desai)

I attempted to transfix this research and essay in slowness. For me, slowness offers a potential resistance to the oppressive and restrictive structures of capitalism. I think of the words of Anne Boyer, cited by Lola Olufemi in episode 94 of the Surviving Society podcast: when asked what the biggest impediment was to writing, Boyer responded capitalism. We must recognise that capitalism places us in a position of continual precarity, of a need to survive, and thus instrumentalise our thinking and creativity in order to do so. When approaching my writing bursary with GRAIN, I was given a fairly open ended and flexible term within which to research and produce a work, yet the continual instability of being a freelancer means that I must position conflicting projects within rigid timelines so as to make ends meet. If I were to let myself, slowness would be my natural state of existing, as due to my mental illness fast-paced and continuous productivity is not available to me. Still, it is difficult to unlearn the pace of capitalism which has conditioned us to whir at 100 miles an hour. This essay then, did not entirely honour slowness in the way I might hope, but certainly sat at an adjunct to slow and gradual learning and thinking, with many of the roots and threads being located over a period of lockdown between March to August 2020.

The following writing is informed by, read through and indebted to the work of Black feminist scholars: namely Tina Campt, Christina Sharpe, Audre Lorde, Saidiya Hartman, Lola Olufemi, Gail Lewis, Rabz Lansiquot and Imani Robinson. Their continually expansive, resistant thinking paves the way for so many of us to better know ourselves and the world around us. I must acknowledge, too, that as a white passing/racially ambiguous mixed-race person my understanding will only ever reach so far. My vision and my perspective is shrouded in the privilege colourism and coming from a predominantly white background affords me. In relation to location, my position as an art curator and writer has been made possible in part due to the relative ease my light-skin brings when working within institutional spaces. If I am obedient, if I am quiet, I am leveraged a greater mobility within white institutional spaces than if my blackness were more explicitly readable. It is important to acknowledge this perspective and privilege as a pretext to an essay which considers and locates an exploration of Black multiplicity, possibility and futurity. Yet, it is also not enough to acknowledge or admit to one’s privilege, we must put in the continual work to dismantle the privilege which enables us to move through the world with greater ease. I am not interested in being passive, quiet or palpable for a white institutional setting, and I will continue to vocalise my resistance to the oppressive forces which structure our sector.

This essay is written in dialogue with, and largely because of Calum Jacobs, through both conversations we’ve shared, research he’s made me aware of, and the support he has extended to me. Thank you Calum for your friendship and generous spirit, I understand myself more fully through speaking with you.

*******

Through May and June 2020 Instagram became galvanised with resource and knowledge sharing around the Black Lives Matter movement. Across my feed, people posted fundraisers, reading lists, useful information around knowing your rights when protesting. Then on June 2nd the whole of the social media platform went dark, as droves of people posted black squares in order to demonstrate their alliance and support of Black lives. The Black Lives Matter hashtag became swamped with these black squares, obscuring useful and at times life saving information (particularly for those out in the streets protesting across the globe). A sea of black squares became a simple and ineffectual way for people to signal their politics; obscuring their daily actions in one fell swoop of performance. Within this, many of us watched as people we had grown up with, who at their best had never before vocalised a condemnation of racism, and at their worst had perpetuated racist and oppressive actions, were compelled to post a black square or be publicly deemed a racist. Simultaneously, institutions and businesses across the world with track records of underrepresentation, marginalisation and oppression took the opportunity to obscure their internal structures with this meaningless performative act.

Blackout Tuesday, as it came to be known, was catalysed by two black women Jamila Thomas and Brianna Agyemang through #TheShowMustBePaused, an initiative to ask the music industry to stop their work for a day to recognise how much they are indebted to and built off the backs of Black artists. For Jamila and Brianna, both of whom work in the music industry, the day also acknowledged the need for Black workers to be able to take time with their families and communities, to rest, to grieve, away from the relentless demands of their jobs. At the same time, non-Black members could take the time to reflect on their position and culpability in the racist structuring of the industry, educate themselves and strategise ways to support the movement. Somewhere along the way the meaning and intention of this became obscured, as did the roots of the day being founded by Jamila and Brianna, in an act which reveals the dangers of social media in simplifying the context of wider movements.

I have always been sceptical of the mechanisms of social media. There has been well documented condemnation of Facebook following the Cambridge Analytica scandal of 2018, in which millions of Facebook users’ personal data was leaked and harvested without their consent, predominantly to be used for political advertising. Instagram, meanwhile, has remained somewhat unscathed despite being bought by Facebook back in 2012. The commodification of people’s lives, with a shift from marketing objects to branding and selling lifestyles, has only been intensified through social media. This shift is perhaps most apparent on Instagram where branded posts and content can lead to “influencers” making an income directly from what they choose to post day to day. On such an explicitly commercial platform, it becomes convoluted to argue for the radical and political organising aspects of social media. Yet, it cannot be denied that Instagram has simultaneously provided a site for people to come together around shared issues, galvanise support for movements, and build meaningful, wide-reaching communities. The platform has also given agency and sources of income generation to people and communities who might otherwise have less access to stability. Creative paths, which have historically been largely dominated by people from privileged backgrounds with financial safety nets, are opened up to people from a range of backgrounds who have a tool at their fingertips through which to generate a lucrative income to support their art. Either way, we are no longer at a point where we can deny the influence and power of an app which as of 2020 has 26.9 million users worldwide. Acknowledging this influence, as well as the integral part the platform has played in organising around the Black Lives Matter movement, what possibilities exist to rupture its commercial and marketable foundations?

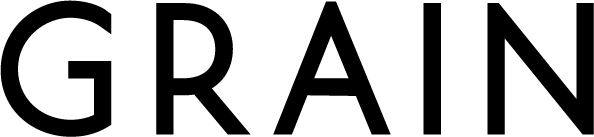

Kai Isaiah Jamal is one such person who is toeing the line between utilising the benefits of social media to fuel their creativity and positioning the app as a force for activism and social change. A poet, writer and model, Kai’s Instagram feed combines activism, poetry, performance and fashion shoots, often fusing all these modes together to catalyse one collective goal of ensuring their voice is heard. On 27th May 2020, two days after the murder of George Floyd, Kai shared a visual poem on their feed entitled ‘TAKE UR FOOT OFF MY NECK’ as response to Floyd’s death. Centre screen, braids long down their chest, Kai sits framed by powerful visual references of Black culture and resistance. A photograph of Colin Kaepernick taking a knee, the NFL quarterback who famously refused to stand for the national anthem in 2016 in protest of racism and police brutality. Initially sitting during the anthem, Kaepernick and his teammates later took to kneeling, viewing this as a respectful gesture and form of peaceful protest. Liz Johnson Artur’s 1991 photograph of a church in Elephant and Castle, a black and white image depicting the congregation in holy attire, knelt in prayer. Boris Gardiner’s 1974 hit Every N*gger Is a Star, plays over the video. A clip from Kahlil Joseph’s 2012 short film Until the Quiet Comes (made for Flying Lotus’ fourth studio album of the same name), which depicts a young Black man who is shot dead but in an act of blissful resurrection continues to dance down the street in slow motion, with passersby framed in still. Images that are ubiquitous in the Black cultural oeuvre, images of explicit resistance and refusal of the extrajudicial murder of Black people, images not of marginality or apology, but that denote the unrelenting power and unmoving agency of Black communities.

‘TAKE UR FOOT OFF MY NECK’, video (still) by Kai Isaiah Jamal, 2020

Beginning with a small pause, Kai then launches into a three and a half minute poem, building up from that first image of Colin Kaepernick taking a knee. Gaining speed and velocity as the poem progresses, Kai embodies and channels the anger and grief of their community, of the grief of another Black life lost and the impossibility in knowing just how devalued your life is to society. There is a relentlessness as Kai lists the unchallenged actions of the police: “They just pull up on a blue badge/They just pull up/They just pull up and pull out and fire and stomp and step on necks/ And turn off body cams/And search bodies that are already dead” as Kai builds pace, demonstrating the unrelenting violence and abuses of power Black people are subject to. Different visual references and contexts of a knee are drawn out, from Colin Kaepernick’s knee of defiance and resistance, to an officer’s knee as a weapon and the question of whether this is the same knee that the white man prays from, through to the shrouding contemplation of “I wonder what it is to be big enough of a God to kneel”. A knee expands into multiple meanings, a visual signifier for violence, resistance, prayer and power, but always coming back to this consideration of the antithetical difference between a Black man kneeling in peaceful and honourable protest, compared to a white man kneeling as an abuse of power, subjugation and wilful dismissal of a Black man’s right to life. In a symbolic act of taking their own knee, in words as opposed to actions, Kai kneels in eulogy, holding commune and space to honour the dead, while simultaneously building protest and resistance into that honour.

What does it mean, then, to come across a visual and aural poem such as Kai’s when scrolling aimlessly through a social media feed? What did it mean to come across this post two days after George Floyd’s murder, when social media was flooded with graphic images of his death? Though Kai alludes to and references the violence and death enacted against Black communities, they do not explicitly or graphically show or depict this violence. I often return to Christina Sharpe’s question, of ‘What does it mean to defend the dead?’ Does it mean to circulate images of their death, in an act of galvanising awareness? No. The very act of sharing the moment when a Black person loses their life, once again signifies how little sanctity and respect is afforded to Black people in life or death. Kai’s poem contributes a visual musing on the collective mourning a community finds themselves in, without further negating the sanctity of Black life. This visualisation, which does not refuse or deny Black death, instead finds other languages and visual cues through which to defend the dead.

Kai’s poem begins with a listing of some of the comments that appear under their Instagram photos: “Someone writes under my Instagram photo, take your foot off my neck/Someone else says, you are stepping on our necks/Somebody else says our necks are breaking, fire emoji, fire emoji.” And it is this rendering of violence and death as casual that Kai ultimately refuses, indicating that these allusions and references to violent acts which appear indifferently on our digital platforms are not casual at all. For as Kai muses “I wonder if there is ever a beautiful Black body that is not disposable.” ‘TAKE UR FOOT OFF MY NECK’ builds rupture into the casual stream of images and allusions to Black death, and refuses this reality as normalised or everyday, in doing so Kai provides a language and methodology for protesting and rupturing the positioning of their life as expendable.

Rhea Dillon, in her 2019 film The Name I Call Myself, comes to images of Black resistance through the modality of celebration (when in situ, the work exists as a dual screen installation which includes a scent in the space). A depiction and celebration of the LGBTQ+ Black community in the UK, with cameos of familiar artistic pioneers (including Kai and Evan Ifekoya, whom I will come to shortly), the film sits as Rhea’s love letter to QTBIPOC. Opening on a slowed frame of a child’s legs running (which is returned to and re-interpreted through different framed perspectives throughout the film) positions the movement of the work into a forward motion, moving into new

expansive spaces and potentials for envisioning queerness and Blackness on screen. That same scene seems to act as a marker throughout the film, signalling a clear spacing out or splitting of the film into several chapters, each creating a paralleled and interlinked consideration of Black Queer life.

The Name I Call Myself, video (still) by Rhea Dillon, 2019

In the first chapter, we come on to a dual screen, of what appears to be a funeral scene. People dressed in black and held in collective mourning (or celebration) of a life. Two figures, paused in movement, close to the ground, proceed to shift and turn into motion while the camera pans ethereally round them as if floating from above. The figures are akin to spirits, and as they move in slowed motion the scene recalls the resurrection of Kahlil Joseph’s Until the Quiet Comes (which, as mentioned earlier, appears in Kai’s visual essay). For Rhea, this opening scene is a recognition of the death of a former self, while also acknowledging all the siblings whose lives have been lost as a result of gender-based violence (notably, with the average death of a trans Black person being 30-35 both in the States and the UK). Rhea finds a language through which to honour the dead, to celebrate the lives of members of the LGBTQ+ community which have been lost, while also indicating the continual transformation which comes when one embraces the entirety of themselves. A mourning and a coming home all at once — or in the word of Rhea ‘A death to the multitude of deaths one has to do to “come out” to oneself and to others.’

The Name I Call Myself, video (still) by Rhea Dillon, 2019

Next, we move through everyday moments of holding commune and ritual: a parent and child doing yoga, meditating, resting, connected in clasped hands, friends sat around talking, laughing and smoking, playing music and dancing together, looking through polaroid photos of a shared life. Cross generational and imbued with a contemplative light, the everyday is sifted through the lens of the extraordinary. Considerations of how we come together are extended in the third section, in which we move from a couple in the back of a cab, tenderly holding hands, with lingering glances at each other’s faces, to a person in the mirror getting dressed, drawing outlines of abs on their torso and a moustache, close-ups to their tattoos with declarations of resistance ACAB andYour Silence Will Not Protect You. Hymns books clasped in hands during a church service sit adjacent to a club night with dancers vogueing. Two formations of places of worship are held in parallel, as we consider where we come to worship and where our faith lies: be that in God, in partnership, in community, in faith in ourselves or in love.

The Name I Call Myself, video (still) by Rhea Dillon, 2019

The final scene appears as a beauty pageant, a single chair situated in the centre of a stage, red velvet curtains and a spotlight framing a central figure. Successively people take centre stage, dressed in celebration and pride, all unified under a white satin sash reading Zami. Zami, as with other references throughout the film (such as Your Silence Will Not Protect You) is an allusion to Black feminist writer, poet and activist Audre Lorde, and their Autobiography Zami: A New Spelling of My Name in which Lorde writes that “Zami” is “a Carriacou name for women who work together as friends and lovers”. Collectivity, friendship and love, tie the people in Rhea’s film together, and collectively they exist in joy and expansiveness. I want to return to the scene between the beauty pageant, and scenes of worship and faith, in which we open on a London escalator. A figure cascades down the escalator, with the camera focused in on their crown of braids, before walking on to a platform and finally on to a tube. There is an instant familiarity of this scene for anyone who’s made London their home, the everydayness of a repeated journey, and the uniformity of the tunnels threading the city together underground. Here, the meaning of Rhea’s film seems to become clear, an underpinning recognition of the city as home. There is a conflict when thinking about how to take ownership and comfort in a locality which is so harsh, which ejects us and questions our belonging at every turn. The Name I Call Myself refuses to give weight or even acknowledgement to the question of whether we belong. It doesn’t validate the question of Where are you from? with an answer. Instead, Rhea’s film refuses to debate or call into question the validity of the lives of the people it honours: it is pure celebration, pure joy and pure elation, of a community that resists by loving, living and sharing expansively and freely without restriction or inhibition.

The Name I Call Myself, video (still) by Rhea Dillon, 2019

If Rhea’s The Name I Call Myself celebrates the everyday, Evan Ifekoya’s 2019 contoured thoughts hones in on one everyday ritual in particular: rest. Thinking through rest as a methodology for resistance is well versed in Black feminist thought. I think of Audre Lorde’s declaration that Self Care is Self Preservation. Yet, in a sociopolitical context which has depoliticised rest and self-care, rebranding it as a capitalist, wealthy and white beauty industry of face masks and expensive beauty products, it is all the more necessary to attend to the radical underpinnings of rest. Evan feels out these radical underpinnings slowly and attentively. Evan’s arm, their hand and wrist visible, submerged in water, facing downwards and focused in on closely by the camera, but with space around in which you can see ripples of water spreading outwards. A triptych, Evan’s arm central, with different perspectives of the water and surrounding natural space of rocks and plants visible. In the next shot, Evan’s hands and the natural scene have swapped sides, now both arms are visible and instead of being fully submerged, float slightly on top of the water. We get a sense of being held and carried by water and nature. Then we come on to a wider shot of Evan’s neck and head above the water, their shoulders submerged, eyes closed and head tilted back in meditation or rest. The scene is imposed on a wider shot of the water, in a collaged effect.

contoured thoughts, video (still) by Evan Ifekoya, 2019

Across the four minute and 40 second film, these cyclical visual motifs recur, repeated scenes with slight shifts in perspective and framing. Each shot is left for an extended time, expanding out, space to breathe. As the viewer, time slows, we are held statically in a vacuum of time stretching out Ad Infinitum. Halfway through the film there is a shift: Evan is submerged in water once again, but now their eyes are fixed, wide open, staring straight into the camera. Only their head is visible above the water. Colourful flowers are arranged behind Evan’s head, vibrant light blues, purples and reds. The directness of Evan’s gaze and the sharp blast of colour in the natural scene, creates a stark disruption within the overriding stillness of the film. Evan’s gaze contains a heightened awareness, a vision. They are awake. They are acknowledging our presence. They are claiming their agency within this contemplative space. The music shifts, too, from a meditative repeating gong sound, to a repetitive bass creeping in, taking up increased aural space. We come on to a scene of flowing waterfalls, calm, and yet the juxtaposition to the previous stillness creates a rupture within the scene. After such still, the change is palpable, it is an activating, a rebirth, a reawakening.

contoured thoughts, video (still) by Evan Ifekoya, 2019

Watching Evan’s film, I became aware of how much of a rarity it is to sit at a screen, and not be moving at an accelerated pace, clicking through, always consuming more. contoured thoughts acknowledges the sanctity of rest, how radical it is to take a moment to pause, to be still, in a world that demands you are continually switched on, constantly moving. Rest as a radical act becomes more intensified when it is situated in relation to Blackness, for being Black can translate into a need to always be aware, to always be hyper vigilant, in a world that deems you disposable. It is this attendance to rest, as a radical Black methodology, which has become obscured in contemporary society, and it is this which Evan compels us to get back to. Slowing down in this way ruptures capitalist time, which necessitates our value as the level of productive labour we enact as bodies. To rest, to stop, is to resist the oppressive forces which render an “unproductive” body invaluable, and which necessitate the inevitability of premature Black death. Rest resists the devaluing of the Black body, by pausing to care for it, to look after it, to invest in its longevity and capacity for life.

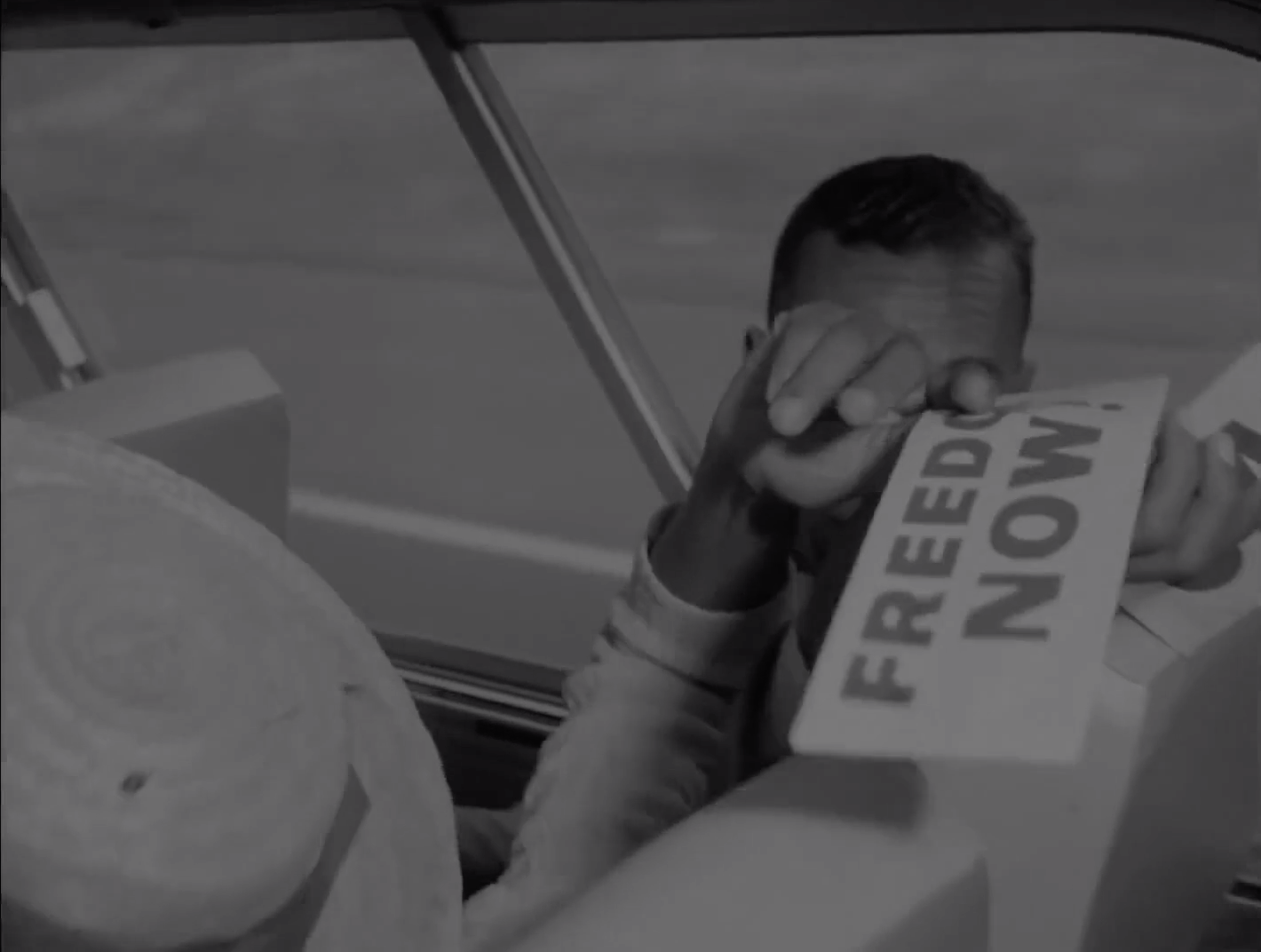

Rupture, then, can also be the opening out of new temporalities. Temporalities which do not attend to the linear moving of time between past/present/future. In Languid Hand’s 2019 film Towards A Black Testimony: Prayer/Protest/Peace, these temporal distinctions are exploded. The film combines a performative speech written and performed by Imani Robinson, with archival footage edited by Rabz Lansiquot (both of whom make up Languid Hands) and a sound mix by Felix Taylor, remixing jazz drummer and composer Max Roach’s song Prayer, Protest, Peace, which features jazz vocalist Abbey Lincoln. Time is undefined, and moves seamlessly between the contemporary and the historical, such as in scenes which interlace archival footage from the March on Washington (1963) and Ferguson unrest (2014). In this exploding of temporal distinctions, Languid Hands attend to how little has changed between these sociopolitical contexts. How the urgent need to get into the streets, to protest and resist the positioning of Black life as expendable, is still as necessary today as it was half a century ago. But this recognition is not defeatist, rather there is an acknowledgement of the many manifestations of intergenerational resistance which exist in the world. From church congregations, to weddings, to marching in the streets, Black communities unify in refusal of the expendability of Black life.

Towards A Black Testimony: Prayer/Protest/Peace, video (still), by Languid Hands, 2019

The text, spoken by Imani, seamlessly combines the words of Black people transposing between past/present/future. Exploring dying declarations, many of the words were spoken by Black people who either anticipated their own deaths or died soon after speaking them. What does it mean then, to have these words live on, taking on new meaning when spoken through Imani? Certainly, there is an acknowledgement of the push and pull of living through “the wake” continually aware of one’s proximity to death. Yet, in another, stronger sense, there is the eternality of these words, which exist outside of time, speaking to multiple generations simultaneously. The Black Chorus, as evoked by writers such as Saidiya Hartman, and by Imani here, immortalises Black voices in collective resistance. Languid Hands engage in mourning, while honouring the resistance of these Black testimonies which reverberate into the past, present and future all at once, refusing to be forgotten.

If we are to understand the discursive, visual and aural practice that Languid Hand’s film is engaged in, we must think through the interplay between speech, sound and image. As Imani speaks the words of Fred Hampton “I believe I’m going to be able to die high off the people” a shot is framed from within a car looking outwards, at what seems to be a police official shining a flashlight across the scene. The light takes over and fills the entire shot, lingering as this passing through and over of light. As Fred Hampton continues through Imani, “I believe that I will be able to die a revolutionary in the international revolutionary proletarian struggle and I hope that each one of you will be able to die in the international proletarian revolutionary struggle or you’ll be able to live in it.” The light subsides, and the wider picture comes back into view, the camera pans out and around to people stood by a car with headlights blazing on, their arms raised in surrender. For a moment the sound drops out altogether, as the camera pans further round to see protestors walking, before a drums comes in distorted and gradual. The collective testimony carries the images, or do the images carry the words, or does Abbey Lincoln’s distorted scream/singing carry both, or do indeed, all three carry us, the viewer, the listener? We are so used to these linear/ straight/eurocentric storytelling practices which distinguish isolated elements to make up a whole, but here they are whole and moving through and forward and backwards and sideways, all at once. We are in the past/present/future simultaneously and nothing is linear or straight. All is cyclical. All moves in waves and reverberations and echoes sliding in and out and through it all at once and on forever.

Languid Hands film takes all the anger, pain and grief, felt by Black communities, and re-situates it as a tool for dismantling the positioning of Blackness as marginal or subjugated. Expansive scenes of a wedding, of people dancing in the streets, held in commune, at church services and baptisms,

while Imani draws upon Audre Lorde’s words on the potentialities of anger. “I have suckled at the wolves’ nip of anger and I have used it for illumination, laughter, protection, fire in places where there was no light.” Towards A Black Testimony: Prayer/Protest/Peace takes this light and makes it universal, translates into the homes of people across the world, and opens out a new radical imagining of a future which is within reach. Where time folds in on itself, this expanding of light touches the present, past and future simultaneously. For we are not separated by generations, our worlds are not so distinct and linear, and as we walk in our resistance we walk alongside our ancestors in their resistance as well.

Let me return again, to attend to slowness once more, because in some ways it seems to linger, to unify each of these works. There is a slowness in Kai’s opening pause as they take a breath before speaking, in the repeated running of three Black children across Rhea’s screen, in Evan’s elapsed, slowed and paused frames, in Languid Hands repeated, ruptured, glitches of archival footage. Towards the end of Towards A Black Testimony: Prayer/Protest/Peace Abbey Lincoln’s scream singing drops out. The silence is palpable after the reverberating echoes of her screams. The screen turns black, Imani’s voice is no longer audible, and all we hear are the faint undertones of the archival audio of Muhlaysia Booker addressing a crowd of supporters. The Black chorus continues on, extending across time and generations. But we are held, as with each film, in a moment of deep reflection and pause. For Tina Campt, slowness isn’t simply an indication of a change in temporality, slowness is attentiveness. Campt writes, ‘Quiet registers sonically, as a level of intensity that requires focused attention.’ Here, in this slowness, in this quiet, is the site where the true potential for rupture sits. Slowness, as Campt marks it, as ‘an ethics of care’, as a methodology ‘to take care of what is overlooked’. Campt compels us to use slowness as ‘a framework for understanding Black life’, as ‘slowing down Blackness’, for it is in this slowing down that we can find the possibility for disturbing the fast-paced, careless positioning of Black life as expendable. It is here that we can understand that Blackness does not sit in close proximity to death, it exists beyond our linear understanding of time, as eternal, as always moving, shifting between past, present and future.

What these works speak to, are not concerns around representational politics. Representation is not enough, for all it does is invites the underrepresented into environments which will only serve to oppress and marginalise them further. More representation does not dismantle the oppressive forces that exist. Instead, these moving image artworks devise a language and methodology of rupture: breaking the restrictions that attempt to hold them statically. None of these works are representational. They do not attempt to reform the mould, they disregard the mould altogether. They build anew from the ground up, an ecosystem which is a sanctum, is refuge, is outside and beyond the mould that restricts us, that attempts to hold and bind us in place, that necessitates our death. Finally, I return to the words of Campt once again and her consideration of tense. If moving image is moving, what is it moving towards? Campt proposes a grammar of Black feminist futurity which ‘moves beyond a simple definition of the future tense as what will be in the future’. ‘Black feminist futurity is a performance of a future that hasn’t yet happened but must’ and here is where these moving image works sit, what they are moving towards — the envisioning and enacting of a future that hasn’t yet happened but must. A future in which the inevitability of Black death has been dismantled, not just in contemporary life, but throughout time. For the future that these artists speak to is now, as it is past and present. Linear time is exploded, and the radical imagining of a future in which we are all free, in which our ancestors are free, our descendants are free and we are free simultaneously. Because as Lola Olufemi reminds us, in our radical imaginings we must ‘ask for everything’ and in their artistic radical imaginings, this is exactly what Kai, Rhea, Evan and Languid Hands do.

Works Cited

Campt, Tina, Listening to Images (Duke University Press, 2017)

Campt, Tina, The Slow Lives of Still Moving Images [Lecture], (Nottingham Contemporary, 2020), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JdKWocqaub4&feature=youtu.be [Accessed 7th October 2020]

Olufemi, Lola, Feminism Interrupted: Disrupting Power, (Pluto Press, 2020)

Olufemi, Lola E094 The Surviving Society Alternative to Woman’s Hour: Lola Olufemi [Podcast], (Surviving Society, July 28 2020)

Sharpe, Christina, In the Wake: On Blackness and Being, (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2016)

About the Writer

Jamila Prowse seeks to interrogate and dismantle the colonialist, racist and ableist structuring of the art sector through filmmaking, curation, writing, and collective organising. Her practice is engaged in collaborating with art workers, as an antithetical method to the alienation of being a BIPOC working within, alongside and adjacent to white institutional settings. Presently, her ongoing research Can We Surv[thr]ive Here? considers the potentials and limitations of institutional work for Black, non-black People of Colour, and disabled artists and art workers, and is informed by Jamila’s own experiences of being a mixed-race curator with lifelong mental illness. As a member of the working group Hypericum: A Code of Practice, initiated by Obsidian Coast, Jamila will contribute to a collectively produced, ever evolving code of practice for feminist, antiracist, anticolonial and environmentally sustainable arts organising.

In 2020 Jamila is the recipient of the GRAIN writing bursary, is Guest Editor of Photoworks Annual 26 and is curating and hosting an upcoming podcast series for Lighthouse. Jamila has curated exhibitions for Peckham 24 (London), 1-1 (Basel), Lighthouse (Brighton) and Brighton Photo Fringe, hosted public programmes for Fabrica Gallery (Brighton), Photofusion (London), Deptford X (London), University of Brighton and Brighton Photo Fringe and written for Dazed, Art Work Magazine and Photoworks. For more information on upcoming work and past projects visit her website.

Photo Credit: ‘TAKE UR FOOT OFF MY NECK’ video (still) by Kai Isaiah Jamal