01 01 2022

OUR PEOPLE, OUR PLACES

*This publication is now sold out.

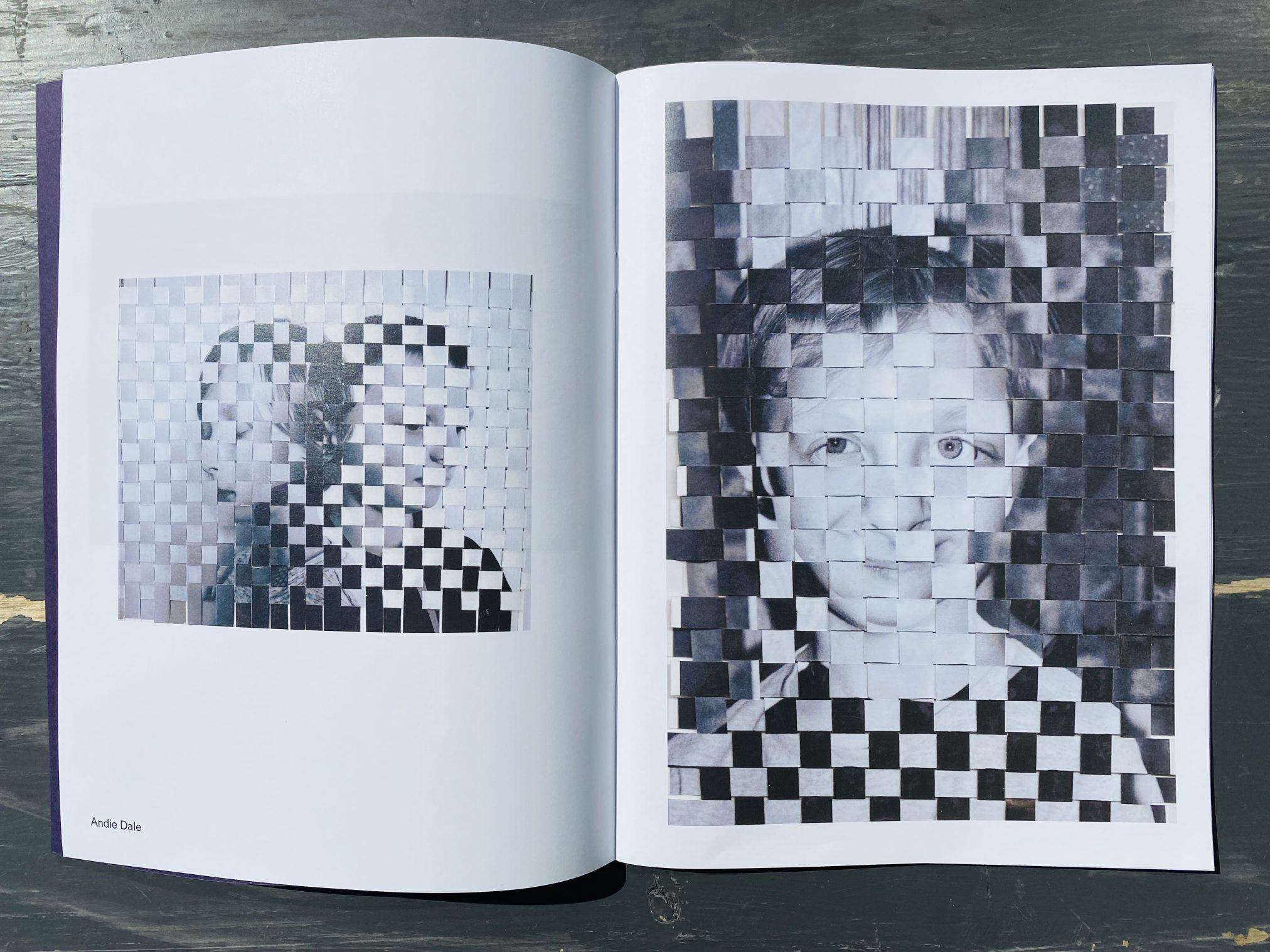

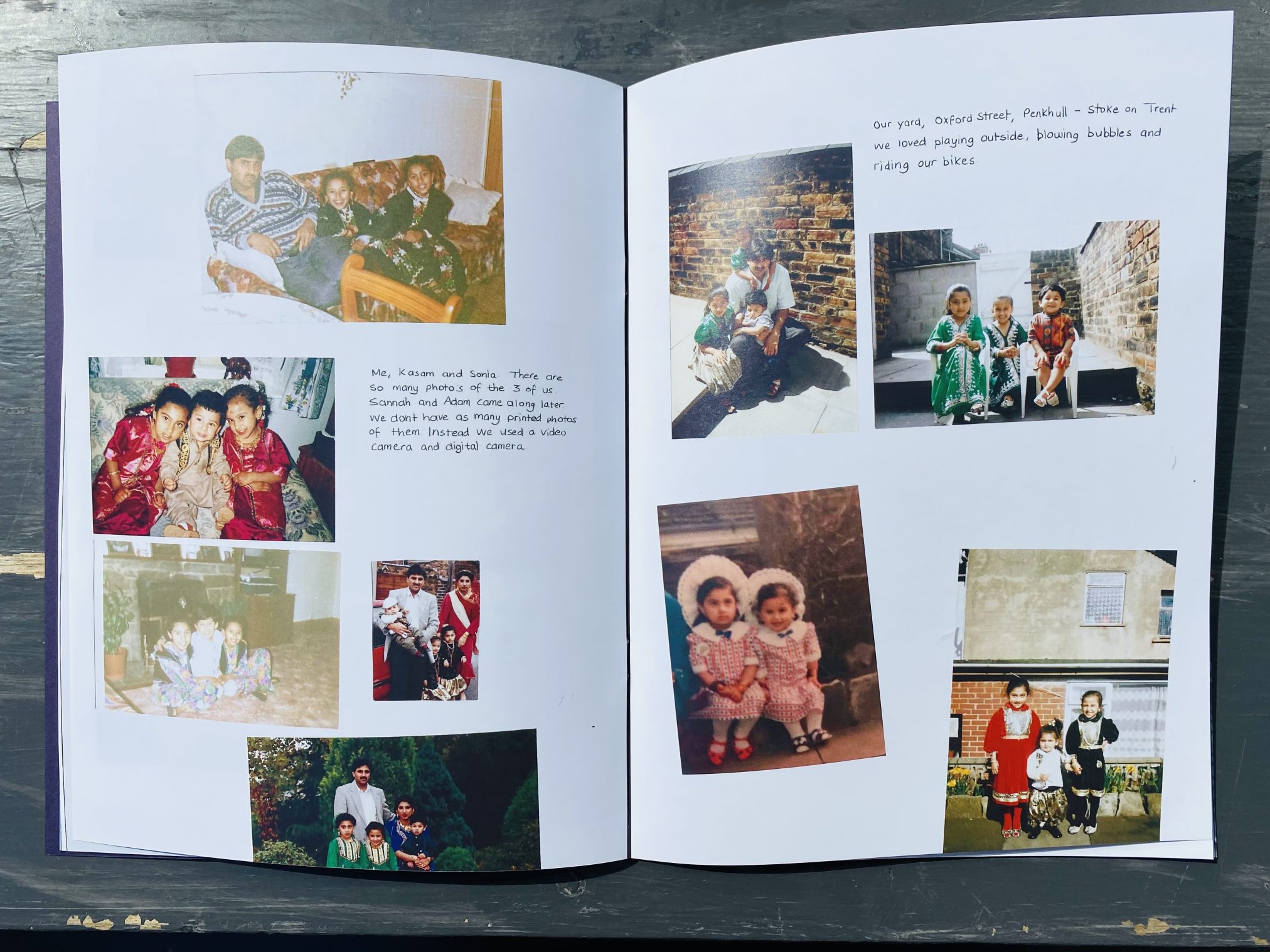

The Our People, Our Places publication is part of a project led by Appetite and GRAIN Projects who invited people to take part in a collaborative photography project about life in Stoke-on-Trent and Newcastle-under-Lyme.

Some of the participants were new to photography, some returning to photography and some wanted to explore photography in new ways.

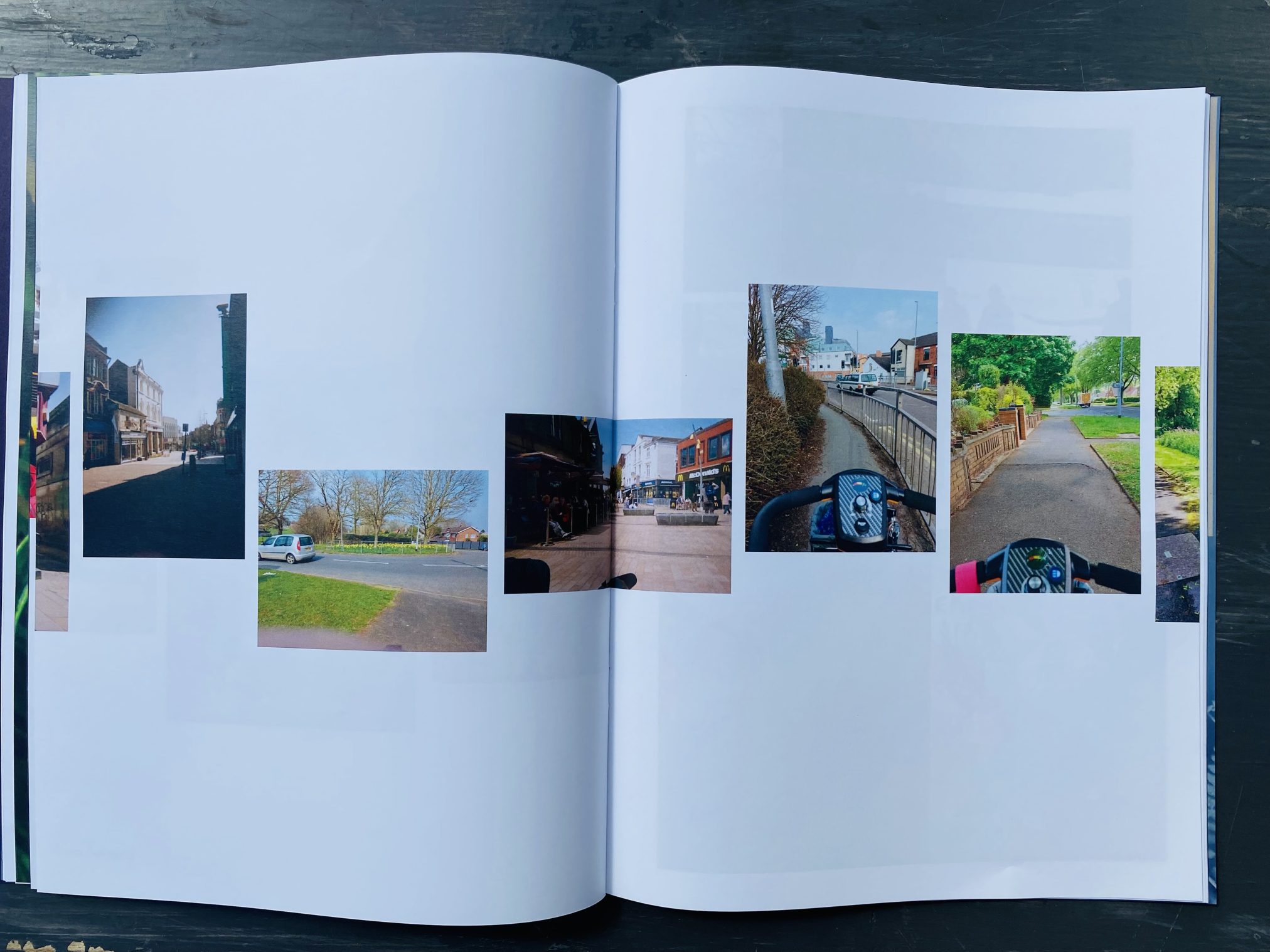

Within the publication there are a wide range of projects that tackle subjects such as family life, history and memories of places and people, landscape, wellbeing, access rights for disabled people and portraiture.

Each of the participants provides a new view and imaginative reflection on the community, people and places that are important to them in their lives. The multiple views shown are a collective vision revealing the broad life experienced within North Staffordshire.

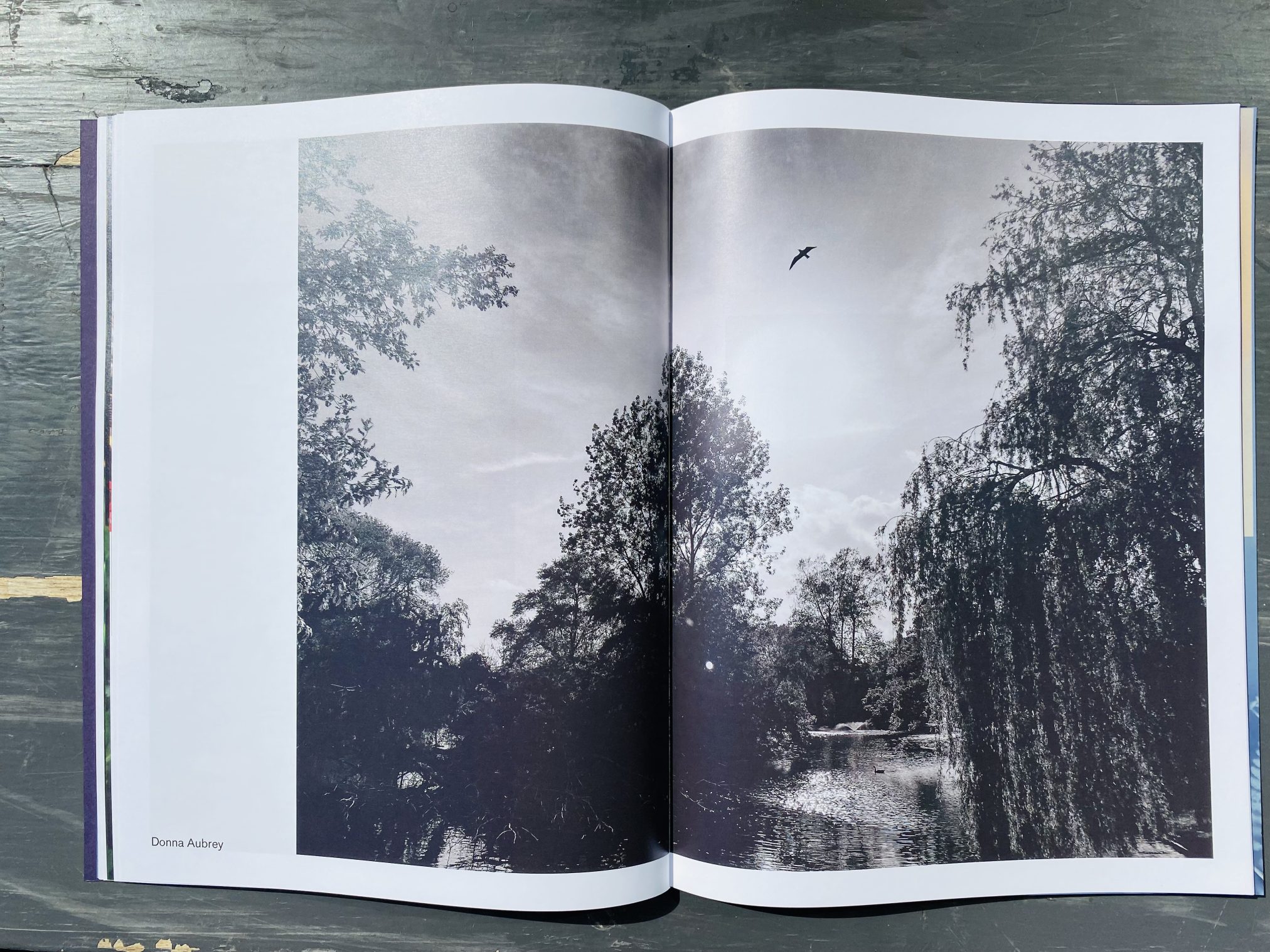

Participating Photographers; Abi Winkle / Andie Dale / Ashley Pretorius / Carol Gallagher / Deb Shenton / Donna Aubrey / Ellie Comber-Davies / Francesca Wheeler / Jo Wade / Judith Pearce / Kaz Hare / Sophia Khalid / Stephen Malkin / Tony Smith.

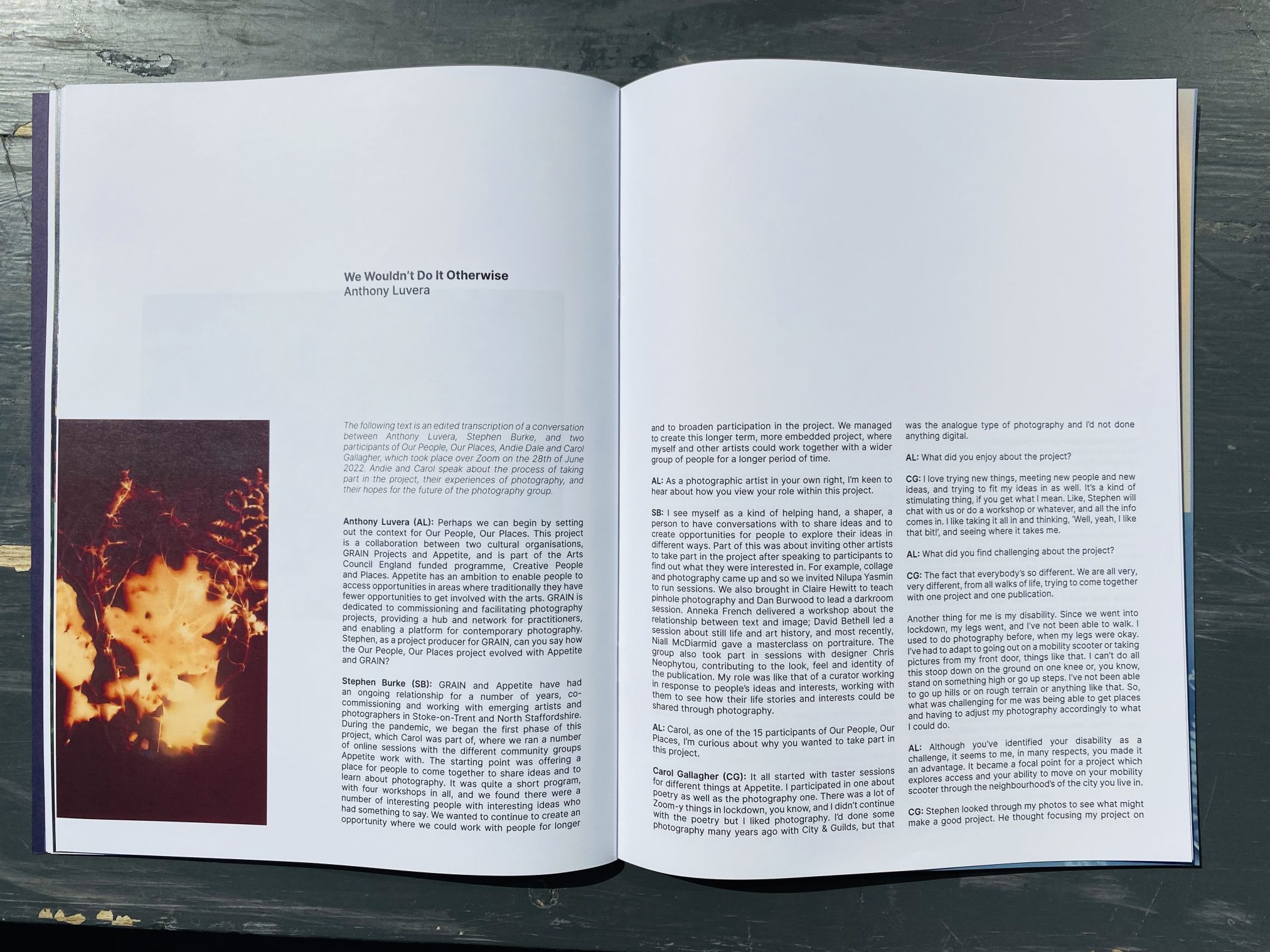

The publication includes an interview by artist, writer, and academic Anthony Luvera with GRAIN Project Producer Stephen Burke and two of the project participants Andie Dale and Carol Gallagher.

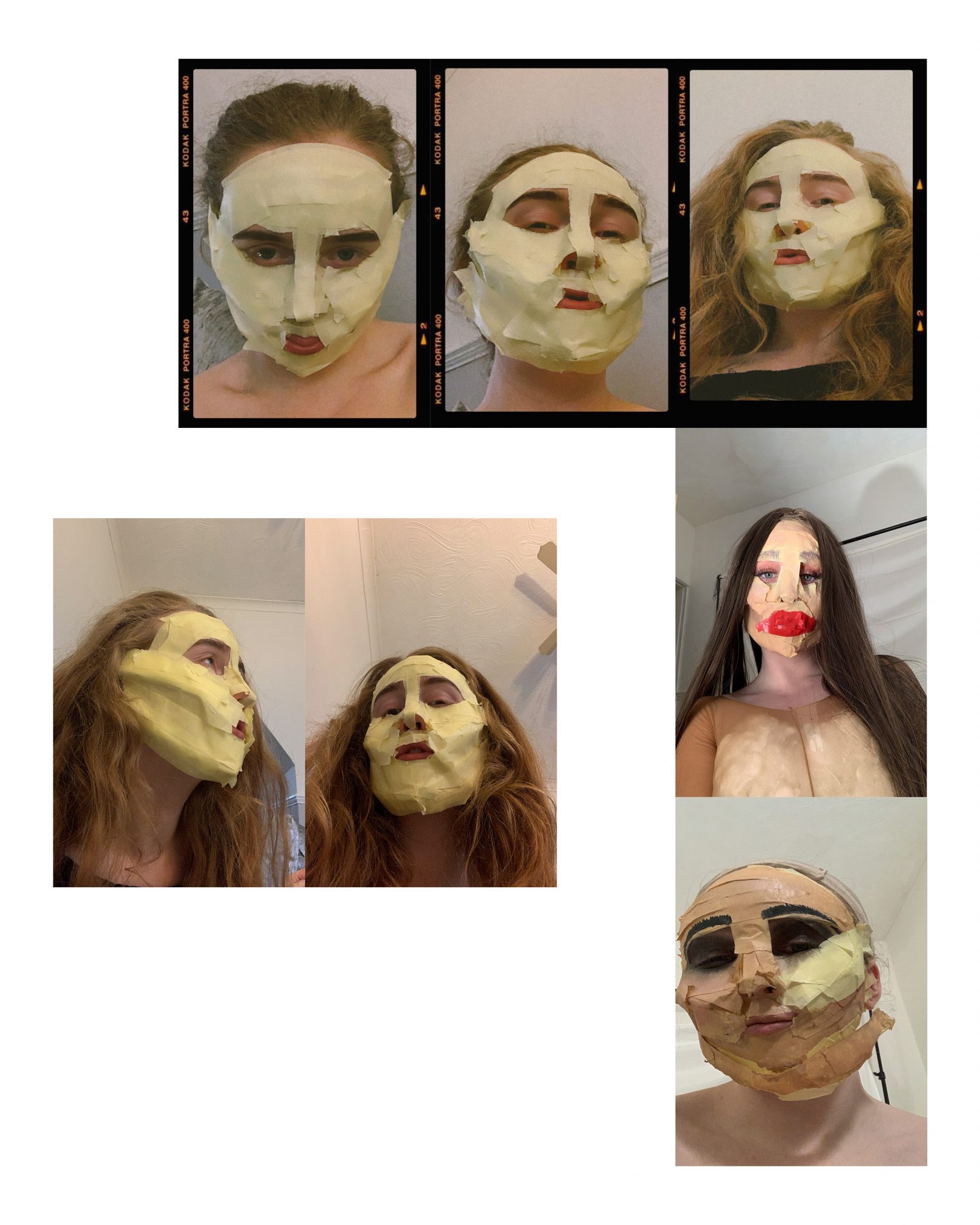

Participants took part in online and in person workshops that took place during 2021 – 2022, led by artists and photographers; Anneka French, Clare Hewitt, Nilupa Yasmin, Dan Burwood, Chris Neophytou, David Bethell, Niall McDiarmid, Stephen Burke and facilitated by Sammy Bishop, Appetite’s Community Participation Co-ordinator, the participants explored a variety of techniques and approaches to photography.

They experimented and made creative work on themes and subjects that were new, meaningful and personal to them, trying out Lumen Printing, Photo Weaving, Landscape, Portraiture, Still Life and Tableau, 5×4 film cameras and printing in the Dark Room.

Key to the project was the participants developing their own photographic and artistic voice, implementing the various techniques learnt, to tell stories that were important to them.

The publication includes an interview by artist, writer, and academic Anthony Luvera with GRAIN Project Producer Stephen Burke and two of the project participants Andie Dale and Carol Gallagher.

Desgin by Chris Neophytou, Out of Place Books.

The project was funded by Appetite as part of Arts Council England’s Creative People and Places National Programme.

*This publication is now sold out.

19 12 2021

Photo Play

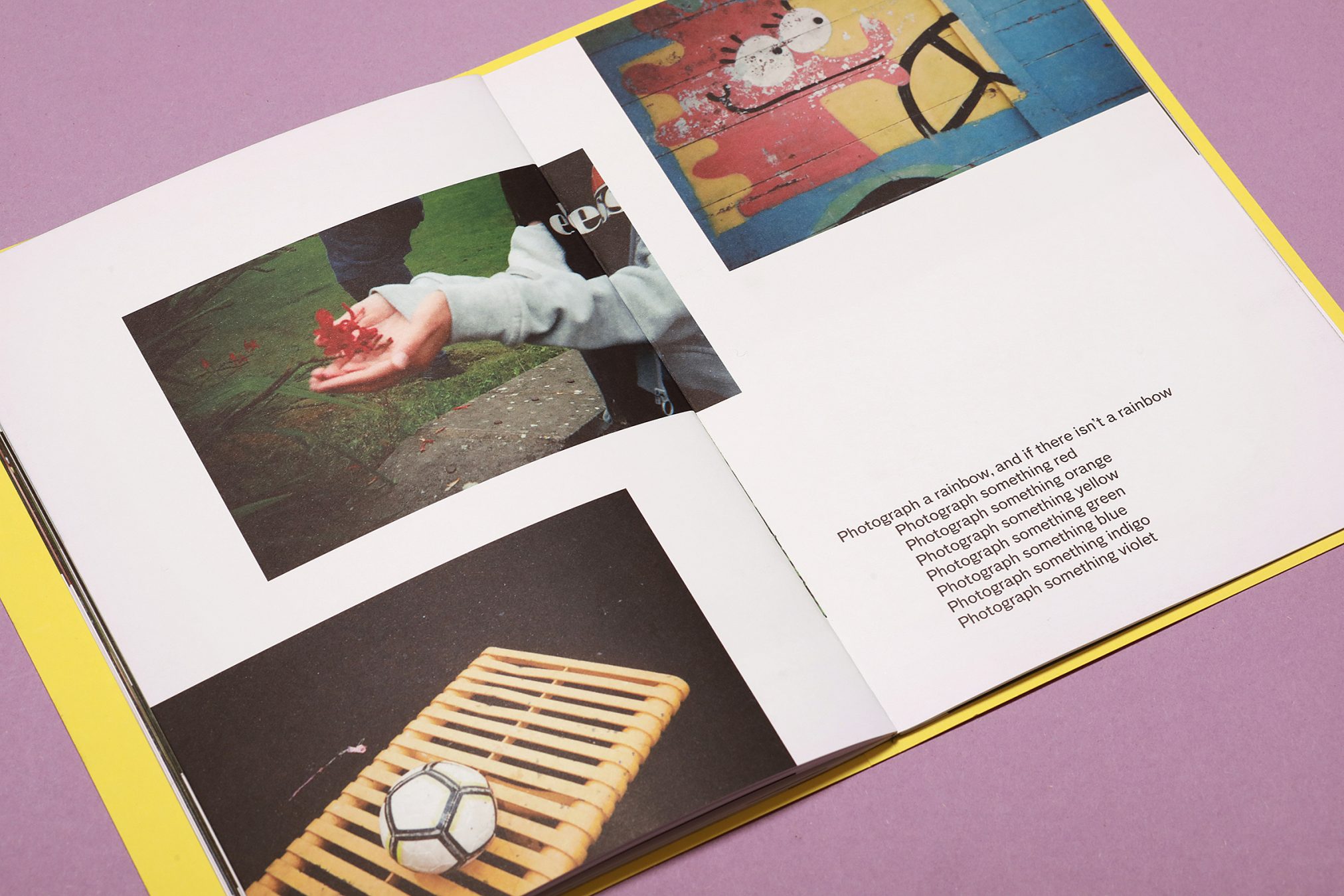

Photo Play is a book of pictures and photography activities for children and young people focusing on play.

In the summer of 2021 GRAIN and Appetite led a series of workshops with children, young people and families in Chesterton, Cobridge, Cross Heath, Kidsgrove and Middleport, in Stoke-on-Trent and Newcastle-under-Lyme.

The images that feature in this book were made by the children and young people who took part in the workshops using disposable cameras, undertaking tasks like the ones you will find in this zine.

We would like to say an enormous thank you to everyone that made photographs with us and took part across the five locations and to thank the artists who led the workshops -Natalie Willatt, David Bethel and Stephen Burke.

The publication will be distributed for free to young people in Stoke-on-Trent and Newcastle-under-Lyme.

Design by Chris Neophytou

21 09 2021

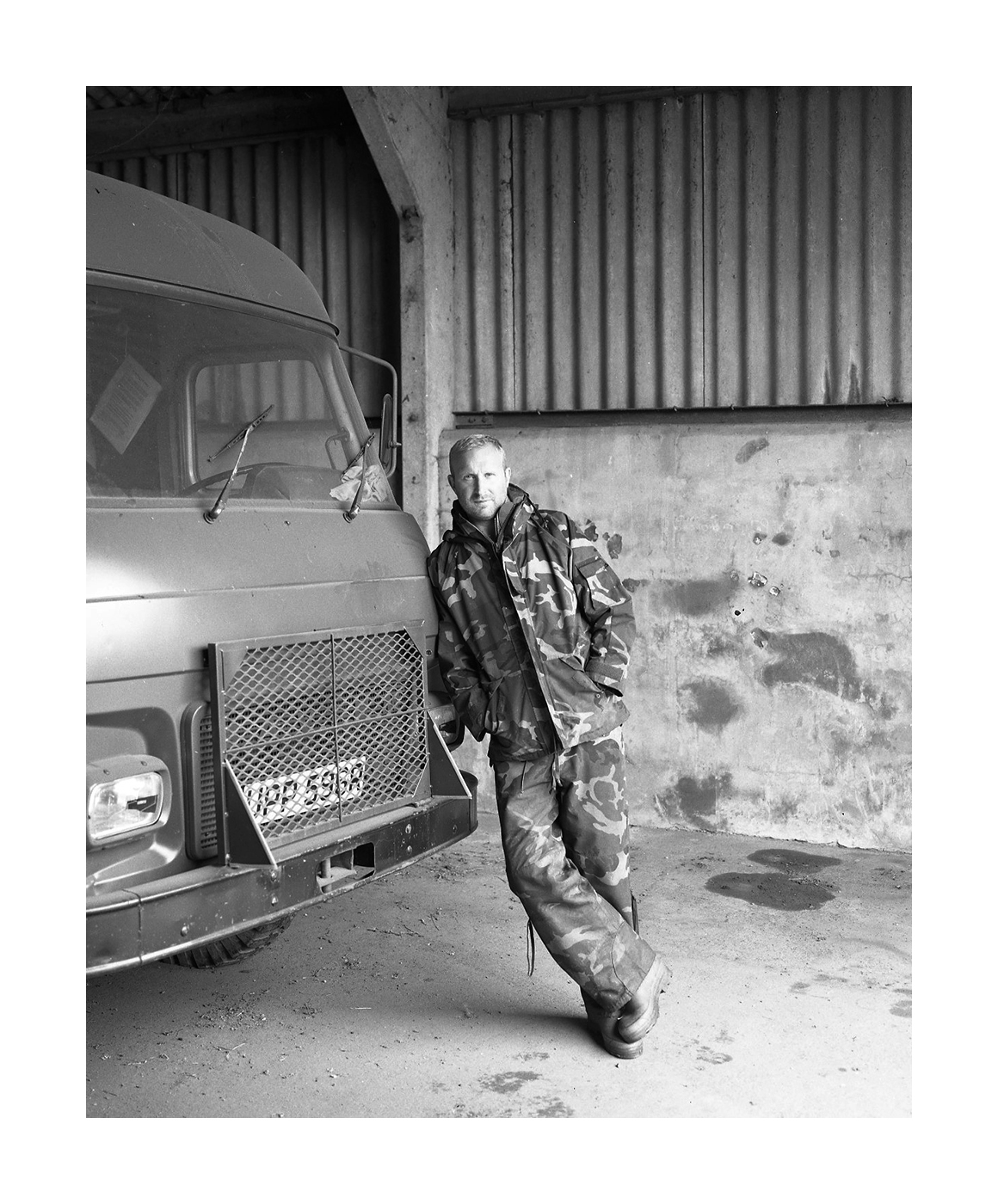

Agency by Anthony Luvera

Agency is a new body of work commissioned for Coventry UK City of Culture which extends Anthony Luvera’s ongoing work made with people experiencing homelessness in towns and cities across the United Kingdom over the past 20 years. Throughout 2021, Luvera invited participants to use disposable cameras to document their experiences and places in the city that are significant to them. Participants were also invited to use digital medium format camera equipment in order to work on the production of a self portrait for the artist’s ongoing series Assisted Self-Portraits. The final images will be exhibited along Warwick Row, a road containing many estate agents that leads into the city centre from Coventry Train Station, throughout the duration of the HOME festival and featured in a community newspaper distributed freely across the city.

Supported by GRAIN Projects

The exhibition will take place from Fri 08 Oct – Thu 28 Oct 2021 on Warwick Row, Coventry

Image Credit: Ruby Nixon

08 06 2021

Coventry; Visual Stories

Coventry; Visual Stories is by Asia, Aya, Daleen and Mohsin who are service users of the Coventry Refugee and Migrant Centre.

The photographs were created as part of a series of online photography workshops that took place during lockdown 2021. the participants learnt about creativity and expression through photography, about technique, photographic history, and they created photographs in response to their new lives in Coventry.

The participants have created a photographic response to their lives in the city, revealing a snap shot of the place and their relationship to it.

About the Coventry Refugee and Migrant Centre (CRMC):

Coventry Refugee and Migrant Centre (CRMC) welcomes and empowers asylum seekers, refugees and other migrants in Coventry to rebuild their lives and achieve their potential.

Forming from humble beginnings in the back of a local laundrette, the charity has grown exponentially during the past two decades and now assists over 4,000 people each year. This includes destitute families, victims of trafficking, modern slavery, unaccompanied children and those escaping conflict zones from around the world.

This project is part of a Coventry partnership which assists and empowers newly arrived individuals and families so that they can rebuild their lives in their new home. Set up in Coventry in 2014, it started out by supporting Afghan interpreters and their families who used to work with the British Army in Afghanistan.

The UK government then launched the Vulnerable Persons Resettlement Scheme (VPRS) and Vulnerable Children’s Resettlement Scheme (RVC), which resettle vulnerable families and children from countries such as Jordan, Lebanon, Iraq, Egypt and Turkey.

It is formed of local organisations Coventry City Council, Coventry Refugee and Migrant Centre, Coventry Law Centre, Coventry Citizens Advice, Positive Youth Foundation, Foleshill Women’s Training and St Francis Church of Assisi.

Currently, Coventry has welcomed over 600 refugees on the programme, one of the best responses of any local authority in the country.

The workshops were led Sam Ivin, Jaskirt Boora, Liz Hingley and Stephen Burke.

The zines & window vinyl were designed by Lotte Norris

This project has been supported by Coventry City Council, Coventry City of Culture and Arts Council England .

08 06 2021

Coventry; Visual Stories

Coventry; Visual Stories is by Charlotte, Ellie, Jamie, Janson, Prash and Thomas who are all members of Teenvine Plus, a development programme run by Grapevine for young people with autism or learning disabilities.

The photographs were created as part of a series of online photography workshops that took place during lockdown in 2021. The participants learnt about different photographic techniques, used different types of cameras and it was also a space for conversation & friendship where their thoughts, feelings and life experiences of Coventry were shared and discussed.

The young people have created a photographic response to their lives in the city, revealing a snapshot of the place and their relationship to it.

About Grapevine:

Grapevine is an organisation that helps all kinds of people experiencing isolation, poverty and disadvantage in Coventry and Warwickshire. They are a pioneering example of how to help people work together to solve their problems for good. They strengthen people, spark action and shift power across services. They empower local citizens with the skills and confidence to act on what they care about; connecting through their shared humanity, taking power into their own hands and regenerating their communities.

One of their many projects working towards this is Teenvine Plus, an intensive development programme for teens with autism or learning disabilities in Coventry. They help learning disabled youngsters to get the friendships, confidence and skills they need in order to mature into independent young adults able to achieve their ambitions. They strengthen people by uncovering their talents and passions, then use these to create natural networks of community support. Networks that strengthen, bring opportunity and help them take charge of their lives.

The workshops were led Ayesha Jones, Jaskirt Boora and Stephen Burke.

The zines & window vinyl were designed by Lotte Norris

This project has been supported by Coventry City Council, Coventry City of Culture and Arts Council England .

12 04 2021

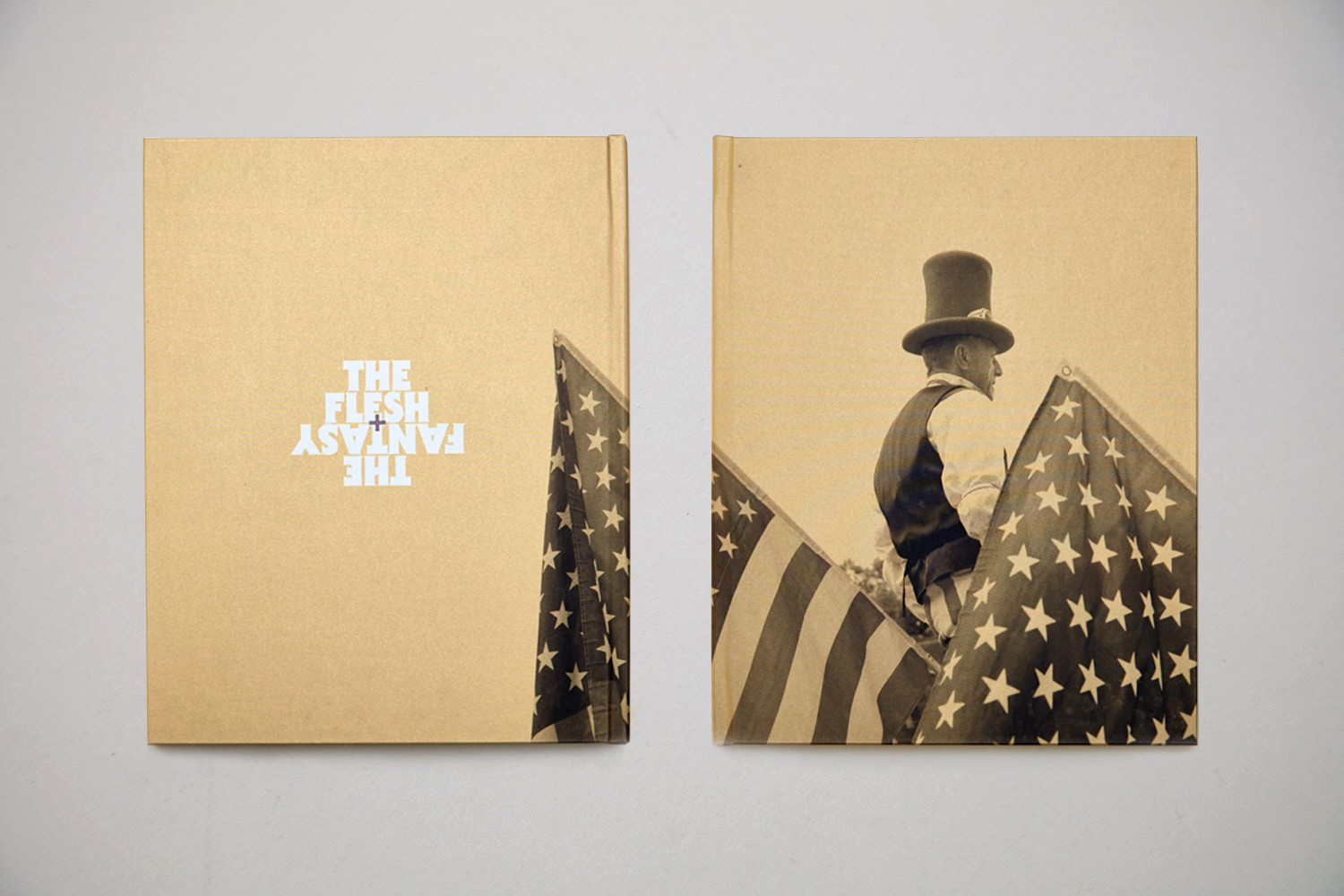

The Rural Gaze

In 2019 GRAIN awarded eleven new commissions to photographers to make new work in rural communities across the Midlands. Using a range of approaches the photographers and artists explored aspects of rural life, culture and community at a time of emergency. Post Brexit agriculture, migration, climate emergency, land ownership and rights, identity and health and wellbeing were amongst the themes explored through documentary and conceptual photography.

Alannah Cooper, Emily Graham, Guy Martin, Leah Gordon, Marco Kesseler, Matthew Broadhead, Murray Ballard, Navi Kaur, Oliver Udy and Colin Robins, Polly Braden and Sam Laughlin.

The projects culminated in a publication and a symposium which disseminate the poetic, documentary, conceptual and archival approaches to photography about the rural that is not dominated by the picturesque, pastoral or romantic but by important new voices that show the complexities, connections and diversity of the rural landscape.

The symposium took place online, hosted by GRAIN and facilitated by academics Camilla Brown and Mark Durden

The Rural Gaze publication is available here.

The Rural Gaze Symposium, Recording – £5.00 , purchase via the Paypal button below:

Image Credit: Around the Stump (c) Murray Ballard

How To Apply?

The residency is a major new opportunity for a Photographer as part of the national Photographer-in-Residence Programme ‘Picturing England’s High Streets’. The opportunity in Coventry is developed by GRAIN Projects in collaboration with the Coventry High Street Heritage Action Zone Board and in the context of a wider programme of High Streets Heritage Action Zone activities.

The residency will contribute to the key local High Street Heritage Action Zone aims including, restoring and regenerating a forgotten part of Coventry’s historic townscape, boosting the local economy and celebrating the city’s rich heritage. The Burges area is the focus and forms a key element of Coventry’s surviving historic townscape. The Coventry High Street Heritage Action Zone project will help reverse decline by enhancing the special character of the conservation area, attracting more business and visitors and raising awareness of the area’s heritage within the local community.

The Photographer-in-Residence will connect with the communities in this distinct area and contribute to the cultural activities that are planned in the lead up to the development of a new heritage square and public space.

Coventry; The Burges, Coventry High Street Heritage Action Zone | Historic England

About the national photographer-in-residence programme

Picturing England’s High Street is a three-year project which includes six photographer-in-residence programmes at six high street locations across England. For more information see Open Call: Historic England, Picturing England’s High Streets – Photoworks.

England’s high streets have a long history and have always been at the heart of our communities. They are our landmarks, points of reference and meeting places. Across centuries people have gathered together on high streets, from market days to turning on the Christmas lights; coffee dates to national jubilees.

Every high street in England, whether it is in a medieval market town or a post-war city centre, has a unique and distinctive history that creates identity and a sense of place. Despite this, high streets are struggling, and need to adapt to survive. This commission will help people reconnect with their high streets, seeing them as places that can thrive and are of relevance to them and their lives.

The photographer-in-residence programmes are a key part of this Picturing England’s High Streets. The six photographers-in residence will work with local communities to reimagine the high street, producing images which will become part of the Historic England archive.

High street users and the community are at the heart of this project and we are looking for photographers whose practice is socially engaged. We are proposing a way of working rather than a thematic or visual approach.

The project starts with a simple provocation; ‘Your high street: Investigate before, picture now and imagine the future……’

We will use this provocation as a creative springboard for a socially engaged, diverse, community led commissioning for the 6 photographer-in-residence programmes.

What are we expecting?

We are looking for a photographer who has an interest in Coventry HSHAZ and whose practice embraces the opportunity to collaborate with the local community. We would welcome applications from socially engaged photographers with a connection to Coventry – although this is not essential.

The Socially Engaged Photographers role will include working closely with local partners to develop relationships with communities to develop visual narratives that are meaningful to them. The photographer will support participants to create photographic stories themselves, through a process of dialogue and collaboration.

Artist Fee – £4,000 over 1 year.

Key dates and timeline

Open call deadline: May 26th 2021

Short list contacted: June 4th 2021

Interviews: June 10th 2021 (TBC)

Start date: Summer 2021 HSHAZ residency begins

End date: End Summer 2023

How to apply

For more information and to apply download the Brief here.

Download Equal Opportunities Form here.

11 03 2021

Covid 19; A Year Lived

During 2020 GRAIN Projects awarded commissions and bursaries to 22 new bodies of work responding to Covid 19 as part of a national programme. Photographers, artists and writers created series, text and imagery responding to and documenting unprecedented times.

Work by eight artists from this programme feature in the exhibition for FORMAT21. They show us the impact on the individual, family and communities, on our health and wellbeing, the inequalities of the pandemic, new ways of working and new closer connections with nature and each other.

Their work focuses on the private, the overlooked and the unfamiliar tropes and imagery of Covid. This is a significant record of life during Covid and the major changes to our way of living and working. Reflecting on and responding to these times as the familiar became unfamiliar the work is an important document of a year lived as never before.

See the online exhibition here.

Andrea G Artz: Pandemia to Pandemia. Artz’s commissioned work features sculptural forms made from her photographs, created as moving image works. The artist travelled on public transport throughout the pandemic to make photographs and interview people capturing their emotions and vulnerabilities.

Barnaby Kent: All People Are Like Grass. Kent’s work looks at the experience of Covid and the onset of lockdown coincided with the start of spring. Throughout the pandemic we witness the annual seasonal cycle and become aware of the essential need for access to nature.

Chris Hoare: Street Cleaners. Hoare photographed the undervalued workforce that helped keep our society going, choosing to photograph street cleaners who kept our environments, cities and streets clean during the pandemic.

Chris Neophytou: The Planting of a Fig Tree. Neophytou made work with the Greek Cypriot community in north Birmingham focusing on how the challenges of Covid-19 affected this community as people adapted to the challenges of practicing their faiths and at the distance felt between the UK and family and heritage in Cyprus.

Jaskirt Boora: Birmingham Lockdown Stories. Boora is a British Indian photographer, her work documents the community around her focusing on how people have come together to offer support and care for each other. Her motivation was to extend the feeling of good will and togetherness she experienced.

Jemima Yong: Field. Yong’s work was made in lockdown in London as she photographed the view from her bedroom window, witnessing how the same public space was being used and shared throughout 2020. Social distancing, face covering, exercise, team sports and family events feature in a typology of 76 black and white photographs exhibited as a performative work.

Lydia Goldblatt: Fugue. In Goldblatt’s series Fugue, intimacy and distance are key. The works meander, moving back and forth through the signs of routine, love and care that bear witness to family life. Chronological time, normally linear and clear, is suspended merging with emotional duration.

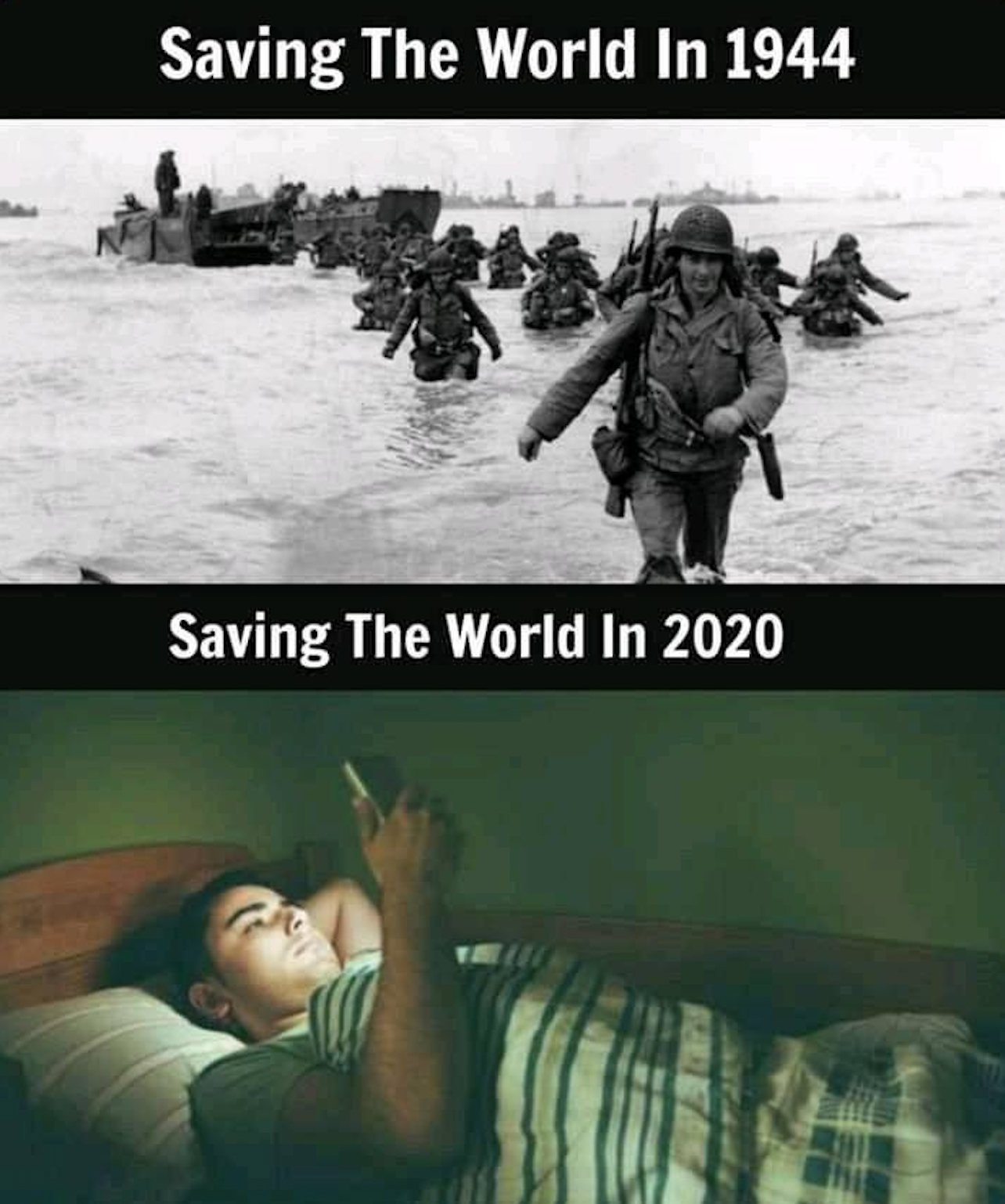

Shaista Chishty: Playing Their Part. Chishty looks at mainstream representations of people of colour during Covid, exploring the visual culture and tropes and the racialised press and media coverage, drawing comparisons with the propaganda of the British Empire and World War II.

In 2016 GRAIN commissioned artist Edgar Martins to respond to HMP Birmingham, the site and community. Over a number of years Martins created a significant, multifaceted body of work developed from many visits with prisoners, staff and their families.

HMP Birmingham, on starting the project, was the largest privately run, category B prison in the UK. During the duration of the project, and in response to various crises, the government took back control of the prison. Using the social context of incarceration as a starting point, Martins explored the philosophical concept of absence and addressed a broader consideration of the status of the photograph when questions of visibility, ethics, aesthetics and documentation intersect.

From a humanist perspective the work seeks to reflect on how one deals with the absence of a loved one, brought on by enforced separation. From an ontological perspective it seeks answers to the following questions: how does one represent a subject that eludes visualisation, that is absent or hidden from view? And what does it mean for photography, in an epistemological, ontological, aesthetic and ethical sense, if it does not identify with the photographic subject but the absence of it’s subject?

The work shifts between image and information, between fiction and evidence, strategically deploying visual and textual details in tandem so that the viewer becomes aware of what exists outside the confines of the frame.

Across this complex and radical body of work, Martins worked with archives from renowned European institutions, leading Portuguese physicist João Seixas, inmates and their families connected to HMP Birmingham as well as a variety of other individual and organisations such as colleges, community centres, charities, fire departments and young people’s groups.

The work was exhibited during Covid at The Herbert Museum & Art Gallery, during UK City of Culture, at FORMAT International Photography Festival and has toured to numerous major galleries in Europe as well as being shown in the context of art fairs, including Photo London and Paris Photo.

The work has featured in numerous events and symposia hosted by GRAIN, Birmingham City University and the University of South Wales.

The project was published as a photobook by The Moth House and is available here.

Artist exhibition tour:

See the online version of the exhibition here .

Photograph by Garry Jones

Picturing England’s High Street is a three year project which will deliver six photographer-in-residence programmes at six high street locations across England, as well as artist mentoring and a digital nationwide mass participation project.

The photographer-in-residence programmes are a key part of this project. The six photographers-in-residence will work with local communities to reimagine the high street, producing images which will become part of the Historic England archive. High street users and the community are at the heart of this project and we are looking for photographers whose practice is socially engaged.

The six photographers-in-residence will be selected via open calls beginning in March 2021. Working closely with Photoworks, Open Eye Gallery, Photofusion and QUAD/Format we will select six photographers via an open call to be part of the six photographer-in-residence programmes working closely with local communities in Coventry and Stoke-on-Trent (GRAIN Projects), Prescot and Chester (Open Eye Gallery), in London (Photofusion) and in Leicester (QUAD/ FORMAT).

The photographer-in-residence programmes will also include mentoring support delivered by Impressions Gallery, PARC (Photography and the Archive Research Centre), Redeye The Photography Network, ReFramed and The Photographers’ Gallery.

Picturing England’s High Street will also include a digital mass participation project due to launch in 2022. More news on this will be announced soon.

How to apply

The Open Calls for Coventry, Stoke-on-Trent, Prescot and Chester will launch in March 2021. Followed by Leicester and London, which will launch in Spring 2021. Please sign up to register your interest and to be notified when each open call goes live.

Register your interest via

Open Calls: Historic England, Picturing England’s High Streets – Photoworks

The residencies will take place at different high street Heritage Action Zone across England. The locations are:

Coventry – working with GRAIN Projects

Coventry is a city with a rich history dating back to the Middle Ages. Now a diverse and young city, and UK City of Culture 2021. Coventry’s buildings tell the story of a proud, innovative past built on peace and reconciliation. Today Coventry is a city of sanctuary, diverse cultures and communities. We are looking to select one artist to work as photographer-in-residence in Coventry. This residency will be led by GRAIN Projects and will draw on their regional expertise and existing connections in the local community. The open call for the Coventry photographer-in-residence will go live in March 2021. Find out more about this opportunity and our partner GRAIN Projects here.

Stoke-on-Trent – working with GRAIN Projects

Stoke-on-Trent is a city in Staffordshire formed by the federation of six towns. Since the 17th century the area has been the home of the pottery industry in England. The six towns are tight knit communities, all distinct with a rich and unique heritage. We are looking to select one artist to work as photographer-in-residence in Stoke-on-Trent. This residency will be led by GRAIN Projects and will draw on their regional expertise and existing connections in the local community. The open call for the Stoke-on-Trent photographer-in-residence will go live in March 2021. Find out more about this opportunity and our partner GRAIN Projects here.

Prescot – working with Open Eye Gallery

Prescot was a market town known as ‘a town of workshops’ because of its diverse commercial activities that included all stages of watchmaking, pottery, coal mining and tool making. The photographer-in-residence programme in Prescot will coincide with the opening of The Shakespeare North Playhouse which is currently under construction in the town and Knowsley’s role in Liverpool’s Borough of Culture status for 2022. We are looking to select one artist to work as photographer-in-residence in Prescot. This residency will be led by Open Eye Gallery and will draw on their existing connections in the local community. The open call for the Prescot photographer-in-residence will go live in March 2021. Find out more about our partner Open Eye Gallery here.

Chester – working with Open Eye Gallery

Chester’s regeneration plan and the High Street Heritage Action Zone is focused around the Chester Rows and surrounding area. We are looking to select one artist to work as photographer-in-residence in Chester. This residency will be led by Open Eye Gallery and will draw on their regional expertise and existing connections in the local community. The open call for the Chester photographer-in-residence will go live in March 2021. Find out more about our partner Open Eye Gallery here.

London – working with Photofusion

We are looking to select one artist to work as photographer-in-residence in London. This residency will be led by Photofusion and will draw on their expertise and existing connections in the local community. More information about this opportunity and details about the open call for the London photographer-in-residence will be released in Spring 2021. Find out more about our partner Photofusion here.

Leicester – working with QUAD/ FORMAT

We are looking to select one artist to work as photographer-in-residence in Leicester. This residency will be led by QUAD/FORMAT and will draw on their expertise and existing connections in the local community. More information about this opportunity and details about the open call for the Leicester photographer-in-residence will go live in Spring 2021. Find out more about our partner QUAD/FORMAT here.

15 12 2020

Familiar Faces by Adina Lawrence

Familiar Faces by Adina Lawrence, is an exhibition in and about Newcastle-under-Lyme. GRAIN partnered with Appetite and Newcastle-under-Lyme BID.

The exhibition captures the familiar faces and the unique welcome of Newcastle town centre through the power of photography. Running from Friday 29 January until Sunday 1 August, the exhibition of portraits will be seen across three sites in Newcastle-under-Lyme; on Ironmarket, High Street – next to the war memorial – and High Street – near to Poundland.

Photographer Adina Lawrence captured the portraits of Newcastle workers in the Town Centre during December 2020; to highlight local retailers, shops and businesses and celebrate the historic town centre as it is now. The images shine a light on the diversity, strong offers, culture and heritage of the town and the businesses’ resilience during the most challenging of times.

The exhibition includes portraits that capture the wide range of businesses across the town centre, from business owners and staff to new businesses starting out, thriving market stalls to established shops who have been operating in the town for up to 500 years, independent unique outlets to international chains.

Access and Useful Info

- Please support us by adhering to our COVID-Safe measures whilst enjoying Familiar Faces: Hands / Face / Space

- Please adhere to the lockdown guidelines by visiting Familiar Faces whilst doing your essential shop or during daily exercise

About Adina Lawrence:

Adina Lawrence is a Black British portrait photographer who makes portraits of people that show character, personality, strength and diversity. Her pictures are compelling contemporary portraits that tell a story. She is based in Stoke-on-Trent and has BA Hons degree in Photojournalism from Staffordshire University.

Instagram – @adinamya

The project is a collaboration with Appetite, Creative People & Places and is supported by New Vic Theatre, Partners in Creative Learning (PiCL), 6Towns Radio, Staffordshire University, Newcastle-under-Lyme BID, Go Kidsgrove, Keele University and Arts Council England.

Exhibition photograph by Andrew Billington

11 12 2020

A TIME OF UNCERTAINTY

Tristan Poyser

Participatory Talk

Tues 29 December at 7pm – The eve of Brexit…

GRAIN are pleased to be collaborating with photographer Tristan Poyser and Art Link, Inishowen, Co. Donegal, Northern Ireland for this participatory event in association with the exhibition at Art Link.

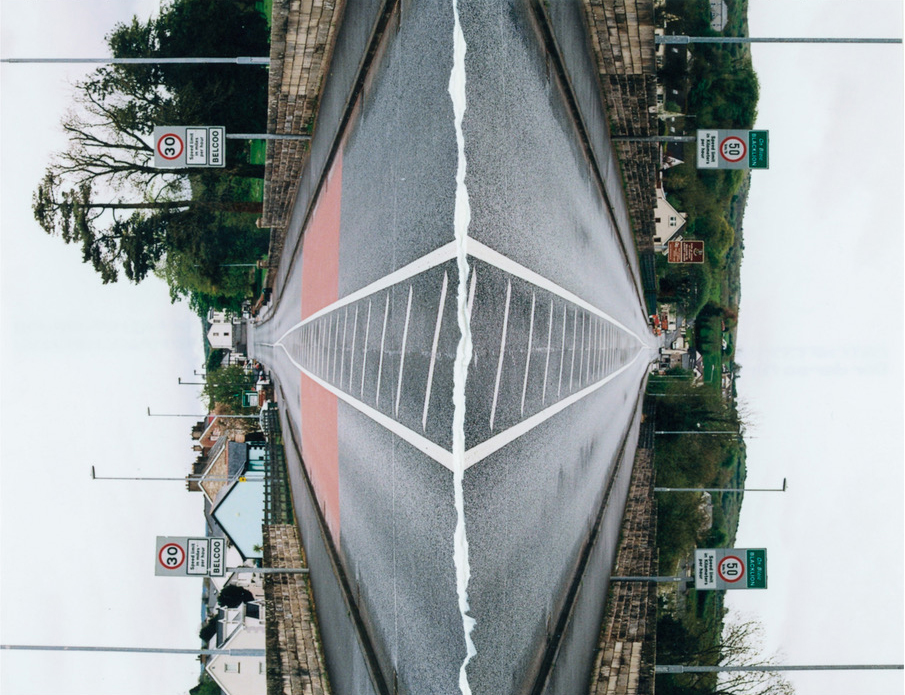

A Time of Uncertainty brings together two significant series of work by Poyser, ‘The Invisible Inbetween’ and ‘Masked’.

Poyser has been making socially engaged work in Ireland, particularly focussing on the border, since the referendum. His work is not traditional documentary but participatory, based on conversations with over 700 individuals and communities over 5 years. For ‘The Invisible Inbetween’ he travelled the Irish border he recorded the landscape reflecting on the effect of Brexit on a land rich with turmoil and history. He explains, ‘Borders are intrinsically peripheries, a third space and projections of the state. The Irish border is both an administrative and political division, an imaginary boundary, with little evidence of the existence to signify a physical border.’

‘Masked’ is a piece that aligns still life, performative portraiture and documentary photography in another idiosyncratic form. 64 masks from his shifts for the online conglomerate Amazon appear bound together. This is a meditation upon an unprecedented era of hardship. ‘Whilst fortunate to be in a position to earn an income, there was a palpable tension brought on by the restrictions of the pandemic, the lockdown and employment. Clocking in, clocking out, timed breaks, compounded by the uncomfortable but necessary safety measures,’ he elaborates.

On Tuesday 29 December you are invited to participate in a Talk that Poyser will be facilitating. The first 50 participants that register before 16th December will receive a pack in the post which will enable them to contribute to this ongoing project link to The Invisible In Between.

Poyser invites the public to consider the referendum vote, their individual vote and how this will impact on those living on the Irish border and their future.

In addition to the first 50 registering you are able to register for the Talk and join in the Q&A and chat.

Each project engages with people and communities and remarks on a crucial time that affects us all. Each is a narrative of opinions, complemented by the artist’s reflection on two dominant issues of our time.

Tristan Poyser is a photographer, a board member of the Arts Council England’s Sector Support Organisation Redeye – The Photography Network, a Tutor for the British Academy of Photography, guest lecturer on Professional Practice, and delivers participatory workshops. He has also judged for the RIBA awards.

To Book | For further information on the associated exhibitions

Thank you to Luke Das who contributed to the text on these projects, interviewing Tristan Poyser for Loupe Magazine.

02 12 2020

Laura Dicken International Bursary

In 2020 Laura Dicken was awarded by GRAIN and New Art West Midlands the International Bursary Award, in partnership with Galleri Image and Aarhus Billedkunstcenter.

Laura has created ‘You Are Another Me’ an inclusive, socially engaged arts project which explores the experiences of women (and female identifying individuals) from a variety of backgrounds who have, for different reasons, migrated alone.

She took an extended amount of time for research and development over the Summer of 2020 to radically adjust her practice so that she can still co-author and co-create with participants in a meaningful way under the new remote circumstances brought on by Covid restrictions. This has been achieved by embracing platforms such as Zoom, Skype, email and WhatsApp.

Working closely with the Aarhus Billedkunstcenter Project Manager, the artist has made connections with local organisations in Aarhus who support migrant women and has invited potential participants to take part in the project. Laura will still collaborate with participants through conversations, shared images and storytelling, but will now do so digitally rather than through in person workshops.

Laura will be delivering an artists talk at Galleri Image and Aarhus Billedkunstcenter remotely in 2021

For this writing commission Lewis Bush looked at the way in which Covid-19 reveals several very significant limitations in the way most photographers think about the medium and what it can and should do. One of these being the idea that proximity produces insight and also the notion that showing something goes any way towards explaining its causes and consequences.

His new writing looks at the visual tropes emerging in the converge of the pandemic and these ideas and highlights what we can and should learn from this crisis as photographers.

Invisible Chains: Photography’s Ingrained Assumptions

by Lewis Bush

In his allegory of the cave, Plato describes a group of prisoners living their entire lives chained in the darkness. Shadowy outlines play on rocky walls, providing the prisoners with their only sense of reality, and they remain entirely unaware of the world outside which created these flickering forms. For Plato, a philosopher was someone who broke their chains and departed from the cave forever.

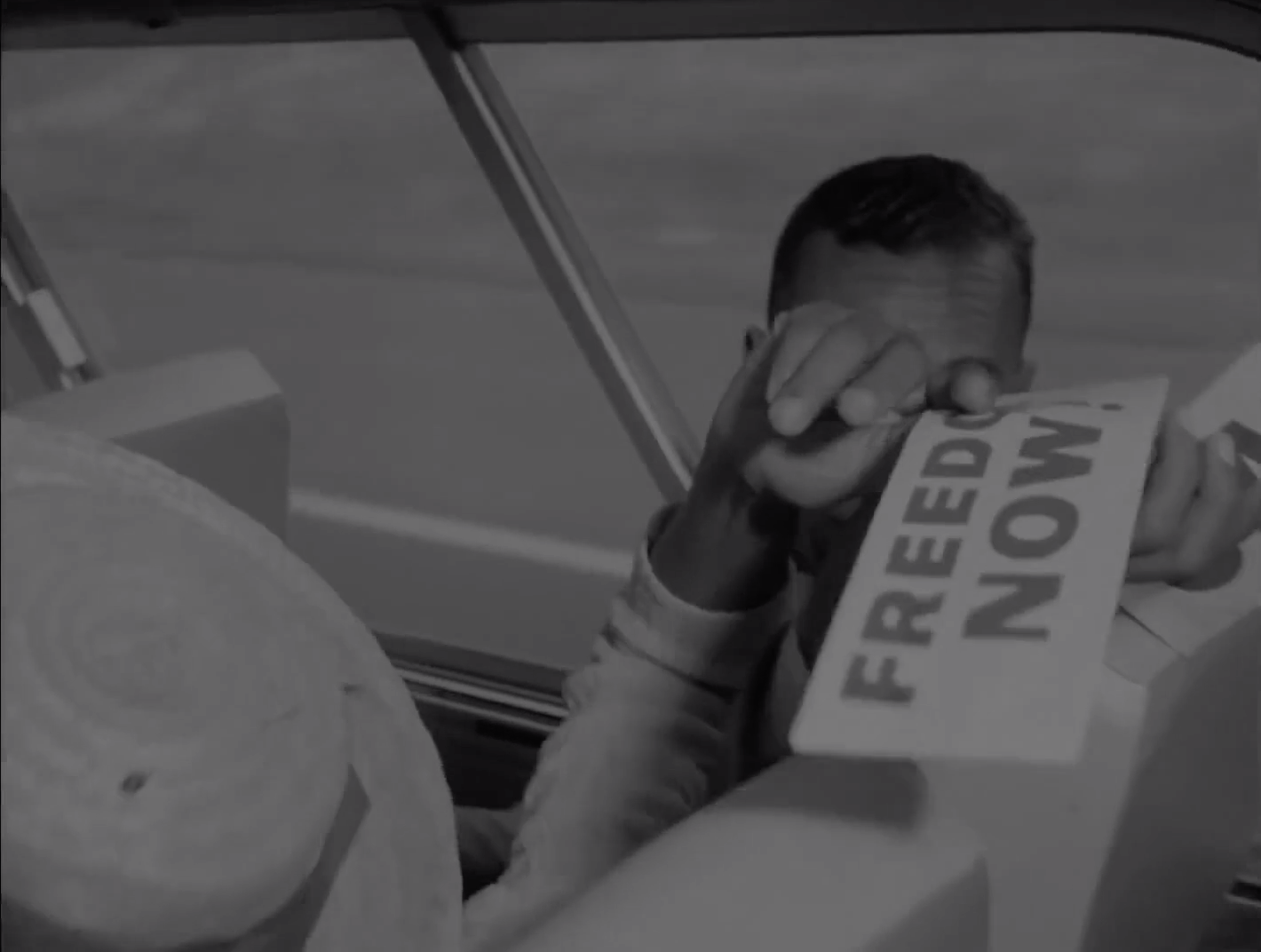

Whenever photography has been a witness to a prolonged and major news event, it has tended to generate a set of visual motifs specific to that story. The global ‘war on terror’ for example gave us the ever-repeating tropes of the aftermaths of terrorist attacks, soldiers enshrouded in clouds of sand and dust, hooded figures kneeling in orange, flag draped coffins, and so on. The creation of these tropes was evidently the result of many factors, choices and filters,[1] but two were particularly important amongst them. One was the specific visual aspects of that conflict, for example it’s locales, belligerents and tactics, and the other one was the particular possibilities for photography in the context of the event, possibilities partly dictated by specific practices like the military system of journalistic embedding and the intentional targeting of journalists by insurgent groups. The images that define the ‘war on terror’ were, in other words, as much a representation of what was photographically possible, as they were the a matter of the best way of visually representing, much less explaining, the subject that was being recorded.

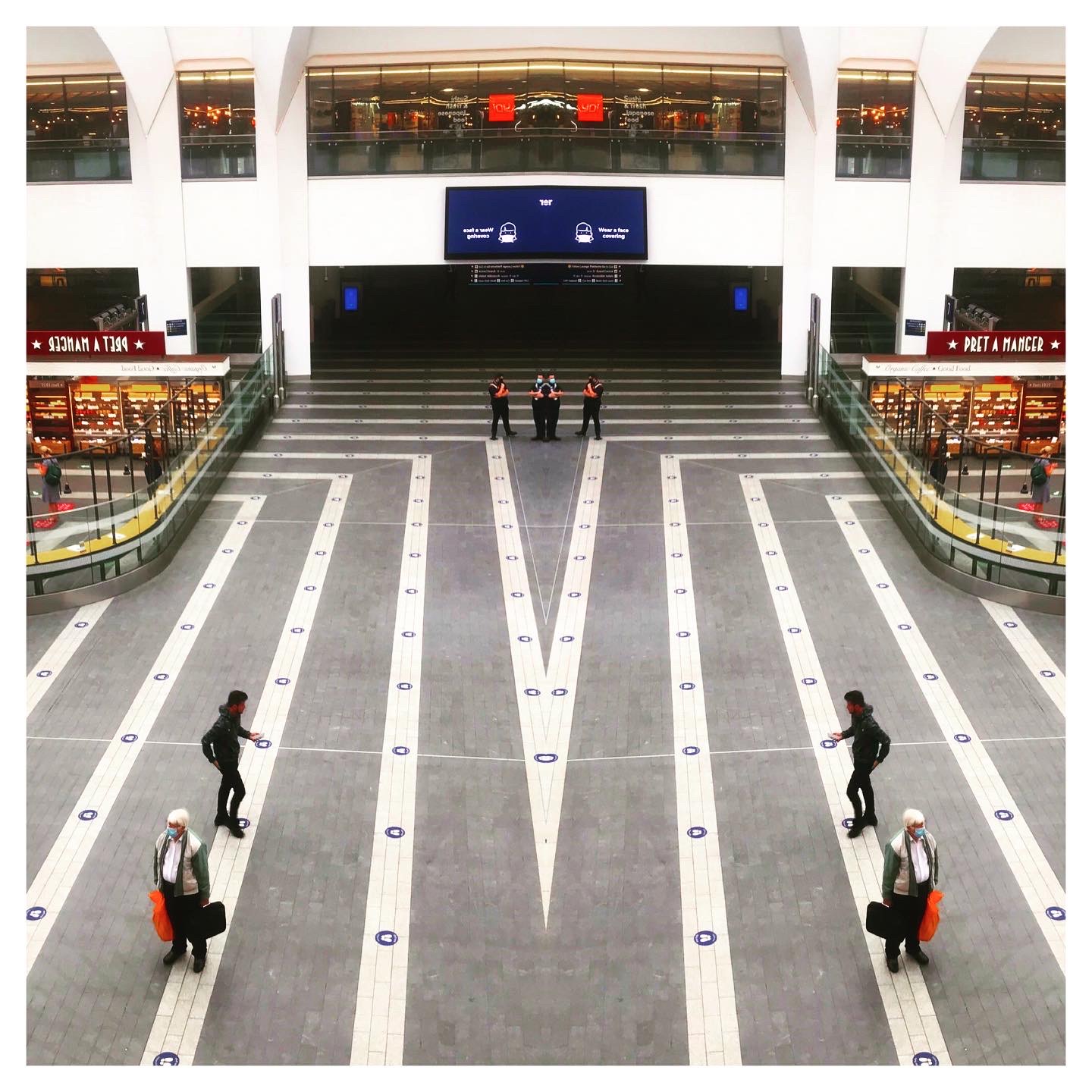

The coronavirus pandemic has been no different in its generation of a set of specific visual tropes, motifs or clichés. I do not doubt that you have already seen many of its examples; People photographed behind their windows and socially distanced on their doorsteps. Photographs of normally bustling landmarks reduced to emptiness. Portrait sessions and other interactions conducted over videoconferencing software. The compressive properties of telephoto lenses manipulated to suggest packs of people crowded dangerously together. Medical staff made anonymous and threatening by layers of personal protective equipment. The list could go on, and on. These image types have been repeated endlessly over the last six months, forming an insidious after image in our collective mind’s eye. They have become an indelible memory of the strange times we have been living through, whether or not it is instructive to remember in these ways. Why, I often ask myself, have few more nuanced responses emerged?

The emergence of such tropes is a clearly a problem with any major news event, but with coronavirus the lack of variety in its representation, and the lack of insight that many of these approaches offer, seems more pronounced than ever. This despite the crisis forcing many of us to spend far more time reflecting on things than we would perhaps have liked, ample time one would imagine for photographers to come up with more nuanced visual strategies. One of the explanations I think is that these images, as much as being a reasoned way of visualising the pandemic, of showing the essential ‘reality’ of it, are also very definite product of the unique limitations that the pandemic places on photography and photographers. In particular and most noticeably the proscriptions in many places on free movement and close contact with other people, two things that photographers rely on more than many of those employing many other means of recording contemporary life.[2] In other words, the photographs that have emerged from the pandemic are again often far from an answer to the question of how best to represent and explain this event and its consequences, and they are much more than usual an answer to the question of what it is possible to photograph under these circumstances.

These visual motifs and tropes are for the most part lacking the perceptiveness they often claim. They provide little or no new insight either into the specific epidemiological profile of the virus, the remedial efforts being put in place by governments and health authorities around the world to stem it, or the personal, social and economic consequences that have resulted from these efforts. We might assume this is because these things are simply beyond photography’s technical capacity to show, but in reality, I suspect it is more difficult than that. The truth I feel, is that these things are actually beyond our imagination to show because we are at every turn constrained and restricted by deep rooted and narrow beliefs about how we should best use photography to explore an event like this one, and all the more constrained because we are for the most part unaware of these constraints. Recognising this could however be an interesting opportunity, because by reflecting on the prevalent clichés in the visual record of coronavirus we might be able to identify the outlines of a few of the hidden ideas that silently shape the creative choices we imagine to be entirely our own.

All human practices are underpinned by certain axiomatic truths, beliefs and assumptions that reflect both the perceived nature of the world we live in, and the imagined nature of the world that we desire to live in.[3] These beliefs are not self-evident, eternal or immutable, they are a product of cultural circumstances, and like all beliefs they ebb and flow with time. They are frequently unrecognised and unspoken, and thus seldom subjected to scrutiny, usually becoming matters of discussion only when something reveals a failure or contradiction within one of them, or when two of them come into direct conflict with each other. Amongst the axioms that underpin medicine, for example, are the beliefs that it is desirable to extend human life, and to alleviate suffering, two assumptions which are usually only subject to significant debate when one of these two aims cannot be achieved without severely compromising the other.[4]

In its own right, photography, and in particularly those genres of photography primarily focused on events in the world, is underpinned its own set of apparently self-evident truths. Many of these concern ideas about the correct way to use photography, in other words what it should be able to do that the other representational tools we have available to us cannot.[5] This is significantly a little different from the often-discussed medium specificity of photography, in that these beliefs do not necessarily need to have a direct relationship to the actual technical qualities of photography (indeed sometimes they ignore these qualities altogether), but in many cases originate elsewhere in society and culture, often in ideas which significantly predate photography’s invention. The problem with these beliefs, and the value in exploring them, is that they shape and direct the ways we use cameras and photographs in ways which sometimes prevent us using photography as dynamically as we might, and as a result undermine rather than strengthen the goals we seek. For this reason, if no other, we should try to draw them out and assess quite how useful they are.

Photographers generally show little willingness or ability to even acknowledge that such beliefs exist,[6] but the global coronavirus pandemic has, quite unintentionally, brought many of these axiomatic truths to the fore, by revealing some of the contradictions and inadequacies within them. Perhaps the most important of these underlying assumptions, are beliefs about the way we derive knowledge from the world, something which we might call the Axiom of Sight. With the gradual emergence of empiricism in Europe between the twelfth and eighteenth centuries, direct sensory experience came increasingly to be viewed as the primary source of information about the world. But of the senses, sight quickly came to occupy a place as the first among equals. Visual technologies like photography helpfully extended what human sight could perceive, cementing it’s pre-eminence, but they also created a paradox. These technologies which were often conceptualised in terms of biological optics, also made it increasingly impossible (for scientists at least) to ignore the vicissitudes and shortcomings of human vision. This recognition seems to have penetrated far less into wider culture, and we have inherited an awkward cultural legacy from these foundations, which still invariably equates seeing with knowing.

The vast majority of photographers are still trained in a tradition rooted in the idea that a photograph of something explains to a viewer why that thing exists, how it functions, why it matters to their life, why and how they should do something about it. But very few photographs are capable of even accomplishing a single one of these tasks, and most of those that do exist in the realm of highly functional, technical images (for example medical x-rays, satellite images, surveillance footage) which very few of us spend much time looking at or thinking about.[7] The majority of art and journalistic photography relies on the strategy of either depicting something aesthetically pleasing or morally troubling to engage audiences with an issue, and it is usually believed that in doing so viewers are motivated to action. In practice such images are just as likely to dull viewers into a sense of apathy or paralysis, less because of the dubious phenomena of photographic ‘compassion fatigue’ but often more because such images seldom offer viewers clear means of recourse or action, and given no outlet any sense of outrage or motivation these images might generate is more likely to slowly stale away inside of them.

Photographic coverage of the coronavirus pandemic reveals this most acutely, in that most of it transmits very little information about the virus or its consequences, beyond the things that we largely already know. Arguably this redundancy is made all the more extreme because of the truly global nature of the crisis, and the fact that many of visual tropes to which most photographers have retreated depict situations that many of us have direct personal experience of. This state of affairs suggests at a second foundational belief closely related to the first, which we might call the Axiom of Effects. This is the emphasis on photographing the highly visible consequences of news events and social phenomena, more often than not these consequences being the ‘victims’ of these things, rather than attempting to reveal the root causes or perpetrators of societal problems and ills. Like the previous axiom, this one has a long lineage, running back to and beyond the emergence of prose journalism and its role in the creation of an informed and engaged citizenry, able to participate in the discursive space that Jürgen Habermas dubbed the public sphere.[8] In this space, a citizenry armed with knowledge derived from journalism would engage in informed debate about the issues of the day, reaching decisions which would allow them to shape the political direction of their communities.

The emergence of photography as a news and documentary medium built to a large degree on this existing understanding of journalism’s purpose. We can see it particularly evidently in the use of photography by early visual advocates for human rights and social reform, like Jacob Riis, Alice Seeley Harris and Lewis Hine, who forged the template that many still follow. Yet what we often forget when citing these examples is that their images formed only one part of their battery of communicative techniques, often depending on extensive narrative context in the form of firebrand speeches and extended texts in order to shape their meaning. The effectiveness of photography for these campaigners lay again largely in its ability to bear witness, to shock, and more troublingly in some cases to excite and thrill. It did not lie in its ability to explain, a fact that we seem today to have become curiously impervious to recognising. Even the most successful photo-essays of photojournalism’s golden age, so often held up as exemplars of purely ‘visual’ communication, relied on their pairing with extensive texts, which provided the explanation of the subject matter that the images never could not. Photography shows only a fragment of an event, and even then, usually only those events that lend themselves to the spectacular or the easily visualised. A photography cannot readily show badly formulated public health policies come into existence, nor can it help us understand why government corruption or ineptitude, at best it might manage to show it.[9]

A third and for now final belief we could dub the Axiom of Transparency, the still prevalent idea that the camera is a transparent window on the world. This idea again is one with roots beyond photography, pre-dating at least the industrial revolution, and exists today as a widely held instrumentalist belief that technologies are essentially neutral tools, that stand apart from social, political, or even aesthetic concerns, but somehow untouched by them. Proponents of this belief (which in truth is almost all of us) view technologies as rational embodiments of principles that are held to be universal, like the desirability of greater speed or efficiency, and the assumed universality of these principles is assumed to also make these technologies universal across time and space. The reality, as thinkers including Lewis Mumford and Donna Harraway have shown these technologies embody the knowledge that makes them possible, and embody specific cultural beliefs and assumptions about the world. Photography for example employs single point perspective in a way which emphasises the primacy of a viewer’s perspective, a ‘god’s eye view’ as many observers have described it, and segments and interiorises that view into the space of a four sided frame. This is not a natural or accidental design, it a choice with roots in western ideas about vision and art.

It is true that most people today would regard the idea ‘that the camera never lies’ to be utterly naïve, and many would also recognise that it does not a pure and unmediated relationship to the things that it depicts. But what is the curious that the same people who would profess these views, in their interactions with photograph and cameras, express exactly this belief unspeakingly through their actions. The camera is still instinctively regarded as a transparent window on the world, we invariably take its images at face value, and it takes active engagement to consider and recognise its well-known capacities for deception and its ability to influence the situations it depicts,[10] much less the subtler ways that embodies specific ideas about the world. Put simply we have been programmed to take the camera’s images at face value, and that programming takes enormous effort to overcome. We can see this again in the abuse of the compressive properties of telephoto lenses by unscrupulous photographers, to suggest crowds where clearly none exist.

This text has not intended to create an exhaustive list of these axioms, or even offer a comprehensive discussion of the few that I have speculatively attempted to identify and name. Nor is it in itself an attempt to challenge or change them, because as has hopefully become clear these underlying assumptions are far too deeply rooted in the history of photography, and the broader history of western thought to be dislodged by a single, short text. Even once aware of them, they still remain the well-worn furrows to which an unguarded mind readily returns. Like ruts in a road, they are too magnetically familiar and too easily travelled, for us to simply forget or dismiss them. They will remain our default mode of thinking for an indefinite future, until new ways of thinking emerge which dislodge them, just as they in turn dislodged earlier pre-modern ideas rooted in beliefs about the spirit world and the divine.

I think however that is worth noting that that these previous intellectual revolutions were invariably fomented by wider social stresses, like mass outbreaks of disease, religious reformations and internecine wars. I do not believe that the current epidemic will be the trigger for a wholesale revolution in the way we think about the world, but it might be one factor amongst many that start us on a process of reassessing the usefulness of the beliefs that have shaped our societies for centuries. While we wait for new alternatives to hint at themselves, we each at least address the deficiencies of our current beliefs by forcing ourselves to engage more actively and thoughtfully whenever we make, use and see photographs. We can each choose to consciously recognise the ways that photography is underpinned by a set of beliefs about the world, and we can recognise the fact that these are culturally formed ways of thinking, not incontrovertible and universal truths, even if it we still struggle to imagine alternative ways of thinking.

In doing this, like the prisoners of Plato’s cave, we force ourselves to the knowledge that there are other ways of being outside of the narrow world which we can actually perceive, even if we cannot yet break our chains, and depart our cave in search of them.

[1] For a detailed study of the filters and concerns that shape the selection of images in photojournalism see Zeynep Gursel’s 2016 Image Brokers, an anthropological study of key sites and actors the industry.

[2] Although it’s worth noting that at least some of the photographers have produced these stereotypical projects appear to have broken UK law to create them. During lockdown there was a short and unambiguous list of acceptable reasons for leaving home. Conducting work as an accredited journalist was one of them, but pursuing independent creative projects was not.

[3] For this piece I focus primarily on very ‘western’ examples of these axiomatic beliefs, in part because these are the ideas that I am most able to identify, but also because photography as we understand it today emerged from a milieu formed by these beliefs.

[4] The tensions between these two goals often publicly emerge in High Court cases, particularly highly emotive cases revolving around the care of seriously ill children. See for example the 2017 High Court case over Charlie Gard, and the 2018 case of Alfie Evans.

[5] It’s worth noting again that this argument comes from a heavily western perspective. While not denying the existence of distinct modes of thinking about photography in other parts of the world

[6] A few photography critics and theorists have however. Jonathan Crary’s Techniques of the Observer is a good example exploring the relationship between the emergence of photography and cultural attitudes towards sight. Lorraine Daston and Peter Galison’s 2007 book Objectivity also includes interesting reflections on this.

[7] This fact also gives emphasis to the untruth, still routinely perpetuated by many people who should know better, that photography is a ‘universal’ or ‘democratic’ visual language. At best it is a constellation of languages and their dialects, some bearing a limited relationship to one another, others about as related as Chinese is to French. To understand the interpret the meaning of an orthographic satellite image requires an understanding of very different visual codes and technical principles than interpreting a photojournalistic photo.

[8] Jurgen Habermas, The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere: An Inquiry into a Category of Bourgeois Society (1962)

[9] See the work of Alex Navaly, the recently poisoned Russian opposition politician and anti-corruption campaigner for a rare example of photography used very much on its own terms to assemble compelling evidence of systemic corruption in Vladimir Putin’s United Russia party.

[10] The use of telephoto lenses to misrepresent the proximity of groups at publication locations is an example of this, which has taken in many including even quite experienced photographers.

About the Writer

Lewis Bush works across media and platforms to visualise the activities of powerful agents, organisations, and practices. Since 2012 his practice has explored issues ranging from the aggressive redevelopment of London, to the systemic inequalities of the art world. Recent works include Shadows of the State, which examines the democratic deficit of intelligence gathering, and Wv.B which examines the dark histories of space exploration. Bush has written extensively on photography, and since 2011 he has run the Disphotic blog. He has curated a number of exhibitions and is course leader of MA documentary photography at London College of Communication.

Image Credit: Saving the World in 1944 / Saving the World in 2020

For this writing commission Jamila Prowse asks the question – In these isolating, politically rife times how can photography and moving image be used as a source of hope, as a way of collectivising Black communities, as a way to hold each other digitally and create space for both each other and ourselves? Her new essay analyses theories around the rifeness of images of Anti-black violence, situating the creation of images of Black joy and abundance within this context as a way to question how Black artists envision and imagine new potentialities for a world in which Black lives are not only valued but celebrated.

Moving towards rupture, resistance, and refusal in Black moving image works

by Jamila Prowse

On 25th May 2020 a forty-six year-old man by the name of George Floyd was murdered by a police officer in Minneapolis. The graphic video showing the moment Floyd’s life was taken from him was subsequently shared online, sparking a resurgence in public support for the Black Lives Matter movement. What the video reveals is something that is maddening and heartbreaking, but unsurprising to Black communities the world over: what Tina Campt terms the ‘statistical probability of Black death’. The viral quality of the video documenting George Floyd’s murder exposes that Black people are not afforded sanctity in life nor in death. For many, the denial and avoidance of the positioning of Black people throughout the world was brought to a head. Here, along with the racially motivated killings of Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery, Tony McDade, Dominique “Rem’mie” Fells, Riah Milton and countless others during 2020 and beyond, provided stark and undeniable evidence of the devaluing and disposability of Black life. Yet, this is a lived reality which cannot be denied, buried or avoided for Black communities.

Christina Sharpe, creates a ‘conceptual framework for living blackness in the diaspora in the still unfolding aftermaths of Atlantic chattel slavery’ through her theory of “the wake”. “The wake” holds multiple meanings, but is an overarching acknowledgement that slavery continues to shape and dictate the structuring of contemporary society. Living through this wake as a Black person, means to ‘live near death’, always aware of its looming threat. Thus, in the viral sharing of the loss of another Black life at the hands of the state, the inescapability of premature Black death was once again made visible. As a mixed-race, light skinned person, who is racially ambiguous, living through “the wake” does not mean staring death in the face in the same way as it did for my father or his ancestors. My light skin affords me the privilege of moving through the world without the continual probability of violence enacted against me. Still, as I sat glued to my screen at the end of May, I became overwhelmed and debilitated by the complex trauma of seeing daily visual reminders of the close proximity of my ancestry to death. For my father this proximity was a lived daily reality, with many of his close family losing their lives prematurely as a result of violence, poverty and sickness.

The pain and anger that my father carried with him throughout his life may well have been a contributing factor to his death in 1998 at the age of forty-four. I was three when my father passed away, I am now twenty-five, and reckoning with how little has changed in the world since I lost him dad twenty-two years ago, how much of the atrocities that broke his heart still exist, is a painful knowledge that is by no means unique to me. How do we reckon with this pain, that was carried by our ancestors and continues to live unrelentingly on in the world? In Sharpe’s words: ‘What does it mean to defend the dead? To tend to the Black dead and dying: to tend to the Black person, to Black people, always living in the push towards our death?’ It is this question that guides the following essay. If we are to reckon with, to live through, ‘the contemporary conditions of Black life as it is lived near death’, we have to have routes and methodologies of collective resistance. I am interested in what Sharpe calls the ‘possibilities for rupture’ which exist within the resistance of Black communities living expansively, fully and unapologetically. Of the daily resistances and ruptures which are inherent parts of Black life.

Towards the end of May my good friend Calum Jacobs suggested that a way to process, to honour, the collective trauma we were experiencing, would be to surround ourselves with the writing, thought and art of Black thinkers, artists and academics. I have always been interested in art as a mode of resistance. Art as a sphere of imagining alternative worlds, of envisioning possible futures. I am drawn to moving image and artist filmmaking as a site for the imaginings and limitless potentialities for Black life. No less, in 2020, when moving image presented itself as a resolve of lingering solace. Underpinning the following thinking, is a consideration of the moving of image: the tense in which it is viewed, the tense in which it is located. Informed by the thinking of Tina Campt, who notes ‘To me it is crucial to think about futurity through a notion of “tense.” What is the “tense” of black feminist future?’ Simultaneously, I am preoccupied with Christina Sharpe’s answer to her own question outlined above: ‘What does it mean to defend the dead?’ ‘It means work. It is work: hard emotional, physical, and intellectual work that demands vigilant attendance to the needs of the dying, to ease their way, and also to the needs of the living.’

What follows are a series of encounters I had with Black moving image works between May and August 2020. I had these encounters at home, via the 11-inch screen of my laptop, a tiny portal which cannot contain the expansiveness of the artworks I came into contact with. What are these moving image works moving towards? How is moving image situated in relation to futurity? How does it think us out, away from, and beyond the present moment?

Some notes on location before I begin… (after Jemma Desai)

I attempted to transfix this research and essay in slowness. For me, slowness offers a potential resistance to the oppressive and restrictive structures of capitalism. I think of the words of Anne Boyer, cited by Lola Olufemi in episode 94 of the Surviving Society podcast: when asked what the biggest impediment was to writing, Boyer responded capitalism. We must recognise that capitalism places us in a position of continual precarity, of a need to survive, and thus instrumentalise our thinking and creativity in order to do so. When approaching my writing bursary with GRAIN, I was given a fairly open ended and flexible term within which to research and produce a work, yet the continual instability of being a freelancer means that I must position conflicting projects within rigid timelines so as to make ends meet. If I were to let myself, slowness would be my natural state of existing, as due to my mental illness fast-paced and continuous productivity is not available to me. Still, it is difficult to unlearn the pace of capitalism which has conditioned us to whir at 100 miles an hour. This essay then, did not entirely honour slowness in the way I might hope, but certainly sat at an adjunct to slow and gradual learning and thinking, with many of the roots and threads being located over a period of lockdown between March to August 2020.

The following writing is informed by, read through and indebted to the work of Black feminist scholars: namely Tina Campt, Christina Sharpe, Audre Lorde, Saidiya Hartman, Lola Olufemi, Gail Lewis, Rabz Lansiquot and Imani Robinson. Their continually expansive, resistant thinking paves the way for so many of us to better know ourselves and the world around us. I must acknowledge, too, that as a white passing/racially ambiguous mixed-race person my understanding will only ever reach so far. My vision and my perspective is shrouded in the privilege colourism and coming from a predominantly white background affords me. In relation to location, my position as an art curator and writer has been made possible in part due to the relative ease my light-skin brings when working within institutional spaces. If I am obedient, if I am quiet, I am leveraged a greater mobility within white institutional spaces than if my blackness were more explicitly readable. It is important to acknowledge this perspective and privilege as a pretext to an essay which considers and locates an exploration of Black multiplicity, possibility and futurity. Yet, it is also not enough to acknowledge or admit to one’s privilege, we must put in the continual work to dismantle the privilege which enables us to move through the world with greater ease. I am not interested in being passive, quiet or palpable for a white institutional setting, and I will continue to vocalise my resistance to the oppressive forces which structure our sector.

This essay is written in dialogue with, and largely because of Calum Jacobs, through both conversations we’ve shared, research he’s made me aware of, and the support he has extended to me. Thank you Calum for your friendship and generous spirit, I understand myself more fully through speaking with you.

*******

Through May and June 2020 Instagram became galvanised with resource and knowledge sharing around the Black Lives Matter movement. Across my feed, people posted fundraisers, reading lists, useful information around knowing your rights when protesting. Then on June 2nd the whole of the social media platform went dark, as droves of people posted black squares in order to demonstrate their alliance and support of Black lives. The Black Lives Matter hashtag became swamped with these black squares, obscuring useful and at times life saving information (particularly for those out in the streets protesting across the globe). A sea of black squares became a simple and ineffectual way for people to signal their politics; obscuring their daily actions in one fell swoop of performance. Within this, many of us watched as people we had grown up with, who at their best had never before vocalised a condemnation of racism, and at their worst had perpetuated racist and oppressive actions, were compelled to post a black square or be publicly deemed a racist. Simultaneously, institutions and businesses across the world with track records of underrepresentation, marginalisation and oppression took the opportunity to obscure their internal structures with this meaningless performative act.

Blackout Tuesday, as it came to be known, was catalysed by two black women Jamila Thomas and Brianna Agyemang through #TheShowMustBePaused, an initiative to ask the music industry to stop their work for a day to recognise how much they are indebted to and built off the backs of Black artists. For Jamila and Brianna, both of whom work in the music industry, the day also acknowledged the need for Black workers to be able to take time with their families and communities, to rest, to grieve, away from the relentless demands of their jobs. At the same time, non-Black members could take the time to reflect on their position and culpability in the racist structuring of the industry, educate themselves and strategise ways to support the movement. Somewhere along the way the meaning and intention of this became obscured, as did the roots of the day being founded by Jamila and Brianna, in an act which reveals the dangers of social media in simplifying the context of wider movements.

I have always been sceptical of the mechanisms of social media. There has been well documented condemnation of Facebook following the Cambridge Analytica scandal of 2018, in which millions of Facebook users’ personal data was leaked and harvested without their consent, predominantly to be used for political advertising. Instagram, meanwhile, has remained somewhat unscathed despite being bought by Facebook back in 2012. The commodification of people’s lives, with a shift from marketing objects to branding and selling lifestyles, has only been intensified through social media. This shift is perhaps most apparent on Instagram where branded posts and content can lead to “influencers” making an income directly from what they choose to post day to day. On such an explicitly commercial platform, it becomes convoluted to argue for the radical and political organising aspects of social media. Yet, it cannot be denied that Instagram has simultaneously provided a site for people to come together around shared issues, galvanise support for movements, and build meaningful, wide-reaching communities. The platform has also given agency and sources of income generation to people and communities who might otherwise have less access to stability. Creative paths, which have historically been largely dominated by people from privileged backgrounds with financial safety nets, are opened up to people from a range of backgrounds who have a tool at their fingertips through which to generate a lucrative income to support their art. Either way, we are no longer at a point where we can deny the influence and power of an app which as of 2020 has 26.9 million users worldwide. Acknowledging this influence, as well as the integral part the platform has played in organising around the Black Lives Matter movement, what possibilities exist to rupture its commercial and marketable foundations?

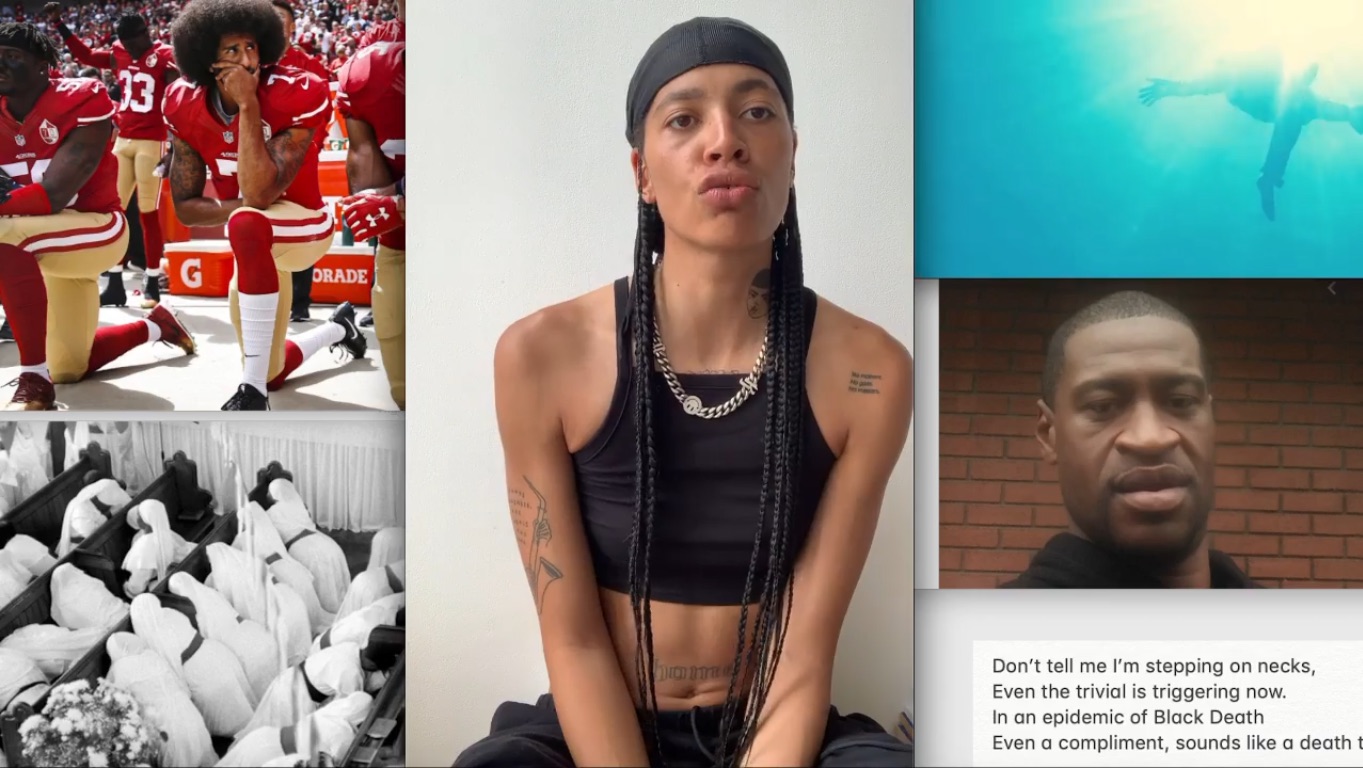

Kai Isaiah Jamal is one such person who is toeing the line between utilising the benefits of social media to fuel their creativity and positioning the app as a force for activism and social change. A poet, writer and model, Kai’s Instagram feed combines activism, poetry, performance and fashion shoots, often fusing all these modes together to catalyse one collective goal of ensuring their voice is heard. On 27th May 2020, two days after the murder of George Floyd, Kai shared a visual poem on their feed entitled ‘TAKE UR FOOT OFF MY NECK’ as response to Floyd’s death. Centre screen, braids long down their chest, Kai sits framed by powerful visual references of Black culture and resistance. A photograph of Colin Kaepernick taking a knee, the NFL quarterback who famously refused to stand for the national anthem in 2016 in protest of racism and police brutality. Initially sitting during the anthem, Kaepernick and his teammates later took to kneeling, viewing this as a respectful gesture and form of peaceful protest. Liz Johnson Artur’s 1991 photograph of a church in Elephant and Castle, a black and white image depicting the congregation in holy attire, knelt in prayer. Boris Gardiner’s 1974 hit Every N*gger Is a Star, plays over the video. A clip from Kahlil Joseph’s 2012 short film Until the Quiet Comes (made for Flying Lotus’ fourth studio album of the same name), which depicts a young Black man who is shot dead but in an act of blissful resurrection continues to dance down the street in slow motion, with passersby framed in still. Images that are ubiquitous in the Black cultural oeuvre, images of explicit resistance and refusal of the extrajudicial murder of Black people, images not of marginality or apology, but that denote the unrelenting power and unmoving agency of Black communities.

‘TAKE UR FOOT OFF MY NECK’, video (still) by Kai Isaiah Jamal, 2020

Beginning with a small pause, Kai then launches into a three and a half minute poem, building up from that first image of Colin Kaepernick taking a knee. Gaining speed and velocity as the poem progresses, Kai embodies and channels the anger and grief of their community, of the grief of another Black life lost and the impossibility in knowing just how devalued your life is to society. There is a relentlessness as Kai lists the unchallenged actions of the police: “They just pull up on a blue badge/They just pull up/They just pull up and pull out and fire and stomp and step on necks/ And turn off body cams/And search bodies that are already dead” as Kai builds pace, demonstrating the unrelenting violence and abuses of power Black people are subject to. Different visual references and contexts of a knee are drawn out, from Colin Kaepernick’s knee of defiance and resistance, to an officer’s knee as a weapon and the question of whether this is the same knee that the white man prays from, through to the shrouding contemplation of “I wonder what it is to be big enough of a God to kneel”. A knee expands into multiple meanings, a visual signifier for violence, resistance, prayer and power, but always coming back to this consideration of the antithetical difference between a Black man kneeling in peaceful and honourable protest, compared to a white man kneeling as an abuse of power, subjugation and wilful dismissal of a Black man’s right to life. In a symbolic act of taking their own knee, in words as opposed to actions, Kai kneels in eulogy, holding commune and space to honour the dead, while simultaneously building protest and resistance into that honour.

What does it mean, then, to come across a visual and aural poem such as Kai’s when scrolling aimlessly through a social media feed? What did it mean to come across this post two days after George Floyd’s murder, when social media was flooded with graphic images of his death? Though Kai alludes to and references the violence and death enacted against Black communities, they do not explicitly or graphically show or depict this violence. I often return to Christina Sharpe’s question, of ‘What does it mean to defend the dead?’ Does it mean to circulate images of their death, in an act of galvanising awareness? No. The very act of sharing the moment when a Black person loses their life, once again signifies how little sanctity and respect is afforded to Black people in life or death. Kai’s poem contributes a visual musing on the collective mourning a community finds themselves in, without further negating the sanctity of Black life. This visualisation, which does not refuse or deny Black death, instead finds other languages and visual cues through which to defend the dead.

Kai’s poem begins with a listing of some of the comments that appear under their Instagram photos: “Someone writes under my Instagram photo, take your foot off my neck/Someone else says, you are stepping on our necks/Somebody else says our necks are breaking, fire emoji, fire emoji.” And it is this rendering of violence and death as casual that Kai ultimately refuses, indicating that these allusions and references to violent acts which appear indifferently on our digital platforms are not casual at all. For as Kai muses “I wonder if there is ever a beautiful Black body that is not disposable.” ‘TAKE UR FOOT OFF MY NECK’ builds rupture into the casual stream of images and allusions to Black death, and refuses this reality as normalised or everyday, in doing so Kai provides a language and methodology for protesting and rupturing the positioning of their life as expendable.

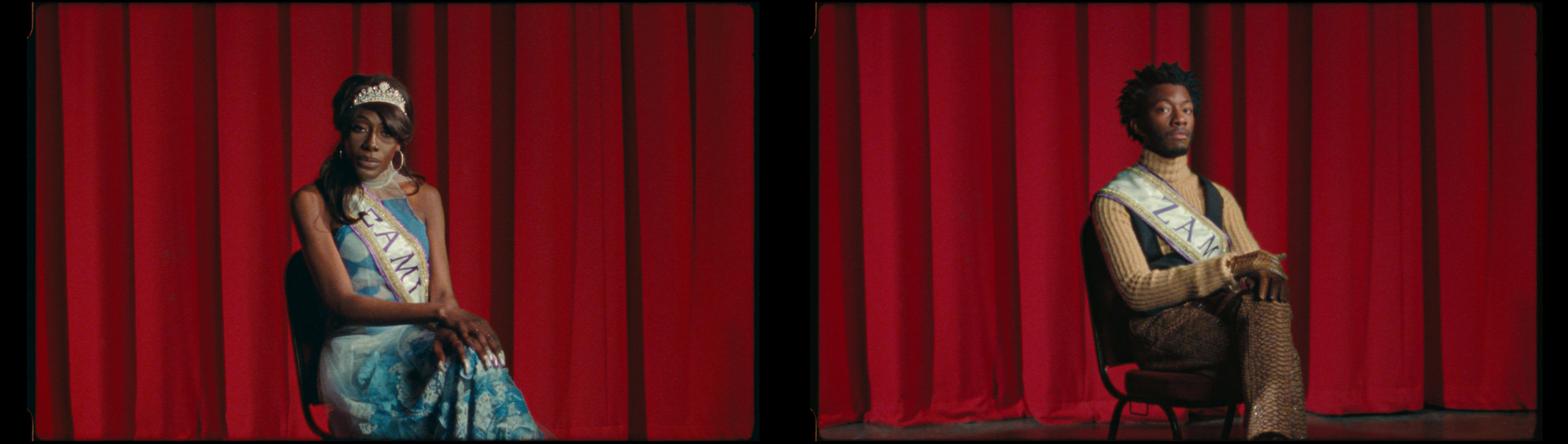

Rhea Dillon, in her 2019 film The Name I Call Myself, comes to images of Black resistance through the modality of celebration (when in situ, the work exists as a dual screen installation which includes a scent in the space). A depiction and celebration of the LGBTQ+ Black community in the UK, with cameos of familiar artistic pioneers (including Kai and Evan Ifekoya, whom I will come to shortly), the film sits as Rhea’s love letter to QTBIPOC. Opening on a slowed frame of a child’s legs running (which is returned to and re-interpreted through different framed perspectives throughout the film) positions the movement of the work into a forward motion, moving into new

expansive spaces and potentials for envisioning queerness and Blackness on screen. That same scene seems to act as a marker throughout the film, signalling a clear spacing out or splitting of the film into several chapters, each creating a paralleled and interlinked consideration of Black Queer life.

The Name I Call Myself, video (still) by Rhea Dillon, 2019

In the first chapter, we come on to a dual screen, of what appears to be a funeral scene. People dressed in black and held in collective mourning (or celebration) of a life. Two figures, paused in movement, close to the ground, proceed to shift and turn into motion while the camera pans ethereally round them as if floating from above. The figures are akin to spirits, and as they move in slowed motion the scene recalls the resurrection of Kahlil Joseph’s Until the Quiet Comes (which, as mentioned earlier, appears in Kai’s visual essay). For Rhea, this opening scene is a recognition of the death of a former self, while also acknowledging all the siblings whose lives have been lost as a result of gender-based violence (notably, with the average death of a trans Black person being 30-35 both in the States and the UK). Rhea finds a language through which to honour the dead, to celebrate the lives of members of the LGBTQ+ community which have been lost, while also indicating the continual transformation which comes when one embraces the entirety of themselves. A mourning and a coming home all at once — or in the word of Rhea ‘A death to the multitude of deaths one has to do to “come out” to oneself and to others.’

The Name I Call Myself, video (still) by Rhea Dillon, 2019

Next, we move through everyday moments of holding commune and ritual: a parent and child doing yoga, meditating, resting, connected in clasped hands, friends sat around talking, laughing and smoking, playing music and dancing together, looking through polaroid photos of a shared life. Cross generational and imbued with a contemplative light, the everyday is sifted through the lens of the extraordinary. Considerations of how we come together are extended in the third section, in which we move from a couple in the back of a cab, tenderly holding hands, with lingering glances at each other’s faces, to a person in the mirror getting dressed, drawing outlines of abs on their torso and a moustache, close-ups to their tattoos with declarations of resistance ACAB andYour Silence Will Not Protect You. Hymns books clasped in hands during a church service sit adjacent to a club night with dancers vogueing. Two formations of places of worship are held in parallel, as we consider where we come to worship and where our faith lies: be that in God, in partnership, in community, in faith in ourselves or in love.

The Name I Call Myself, video (still) by Rhea Dillon, 2019

The final scene appears as a beauty pageant, a single chair situated in the centre of a stage, red velvet curtains and a spotlight framing a central figure. Successively people take centre stage, dressed in celebration and pride, all unified under a white satin sash reading Zami. Zami, as with other references throughout the film (such as Your Silence Will Not Protect You) is an allusion to Black feminist writer, poet and activist Audre Lorde, and their Autobiography Zami: A New Spelling of My Name in which Lorde writes that “Zami” is “a Carriacou name for women who work together as friends and lovers”. Collectivity, friendship and love, tie the people in Rhea’s film together, and collectively they exist in joy and expansiveness. I want to return to the scene between the beauty pageant, and scenes of worship and faith, in which we open on a London escalator. A figure cascades down the escalator, with the camera focused in on their crown of braids, before walking on to a platform and finally on to a tube. There is an instant familiarity of this scene for anyone who’s made London their home, the everydayness of a repeated journey, and the uniformity of the tunnels threading the city together underground. Here, the meaning of Rhea’s film seems to become clear, an underpinning recognition of the city as home. There is a conflict when thinking about how to take ownership and comfort in a locality which is so harsh, which ejects us and questions our belonging at every turn. The Name I Call Myself refuses to give weight or even acknowledgement to the question of whether we belong. It doesn’t validate the question of Where are you from? with an answer. Instead, Rhea’s film refuses to debate or call into question the validity of the lives of the people it honours: it is pure celebration, pure joy and pure elation, of a community that resists by loving, living and sharing expansively and freely without restriction or inhibition.

The Name I Call Myself, video (still) by Rhea Dillon, 2019